This is the first in a series of posts about Langsville Creek, which was Western Creek’s upstream neighbour on the Toowong/Milton Reach. I do not intend to research Langsville Creek fully at this stage, as I have too much still to learn about Western Creek. But I couldn’t resist tracing the path of this (mostly) lost creek and seeing what can be learned by looking at the some of the old maps and aerial photographs. Each post will look at a different part of Langsville Creek. This one focuses on the lowest reaches of the creek, near where it met the Brisbane River. You can also now read Part 2 and Part 3 of the series.

The meanders of Moorlands

Toowong Cemetery … Anzac Park … the Mount Coot-tha Botanical Gardens … Quinn Park … the McIlwraith Croquet Club … Toowong Memorial Park … Moorlands Park.

What do all of these places have in common? The answer is a creek. Not a creek you are likely to have seen or heard of, for there are few traces of it left today. But there once was a creek that flowed through all of these locations.

The creek uniting these locations was known to early Brisbanites as Langsville Creek, though I imagine that it also had names given to it by the Turrbal people long before Europeans arrived. I’ve not read up on how and when it came to be known as Langsville Creek, but given that just about everything else in this part of Brisbane is named after John Dunmore Lang, I’m going to take a punt and guess that this creek was as well.

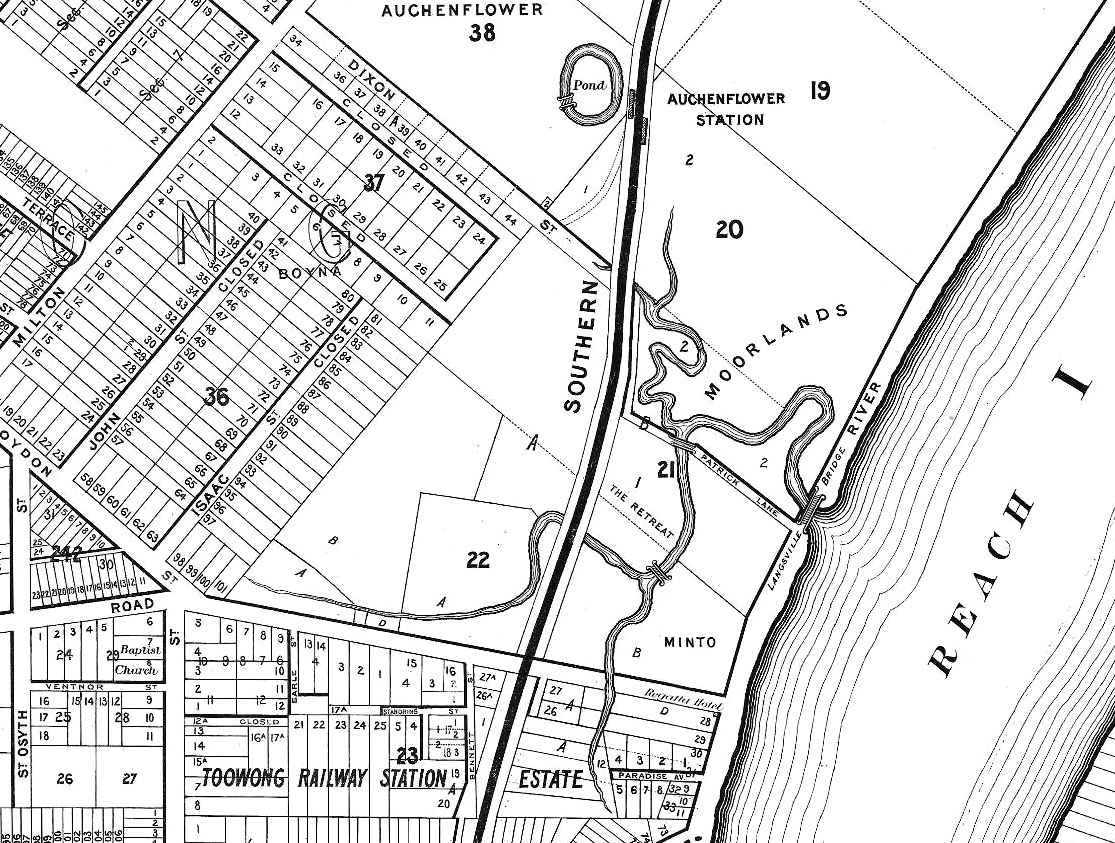

You can see Langsville Creek — or at least part of it — on the early maps of Brisbane. It’s depicted most clearly on McKellar’s 1895 map, the relevant portion of which is reproduced below. The creek itself is unnamed on this map, except by way of the bridge that crosses it where Patrick Lane meets the River Road (now Coronation Drive). The creek looks rather like an outgrowth of the river, as if the river has put out tentacles or feelers, each one meandering through the landscape much as the river winds its way to the bay. The land surrounding it appears to be mostly undeveloped, presumably because it was damp and flood-prone.

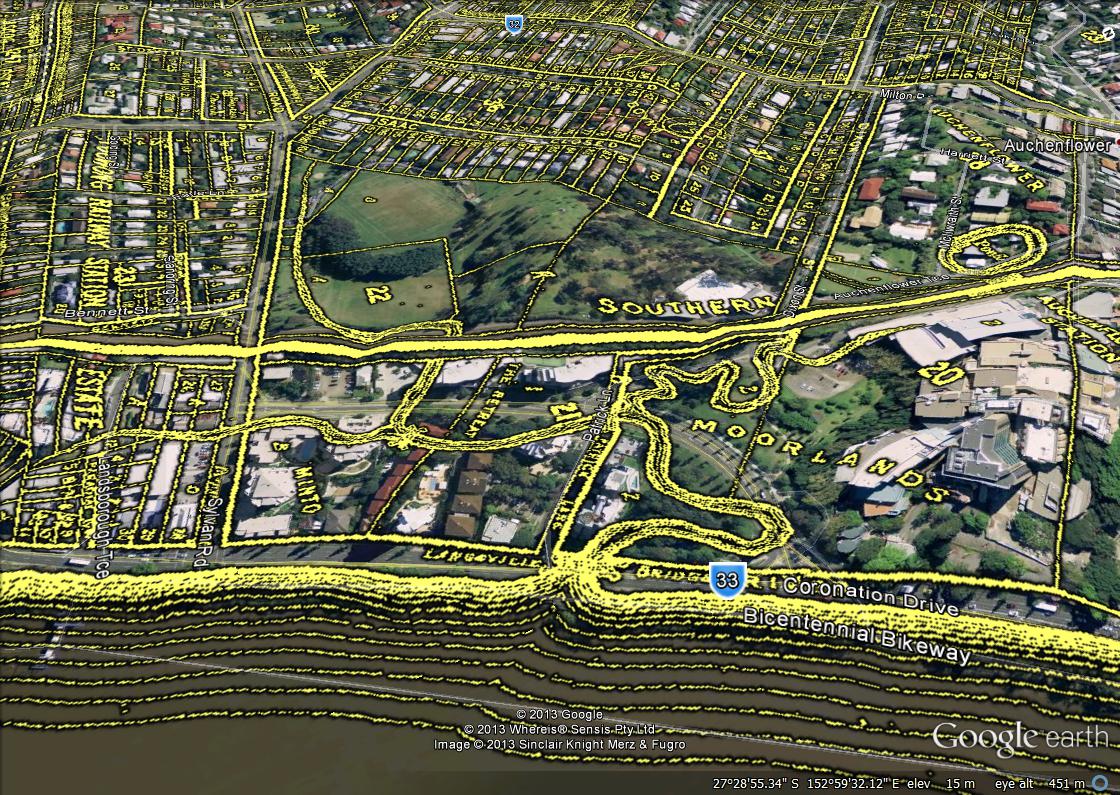

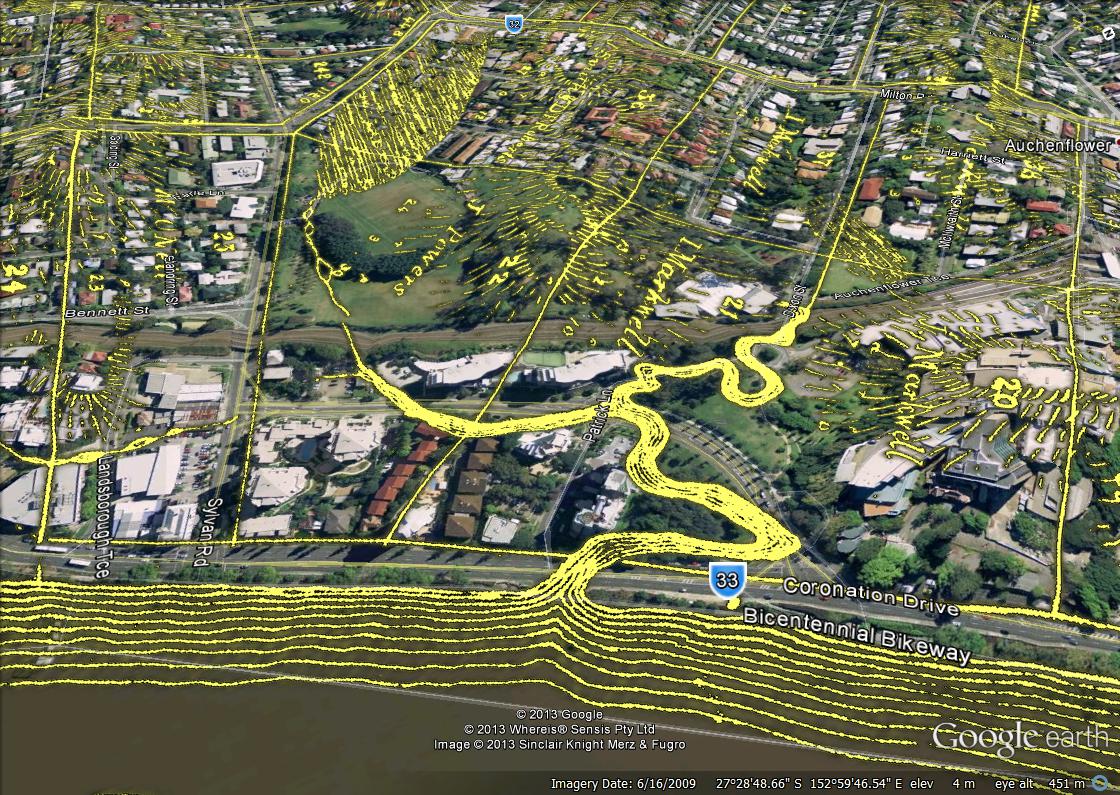

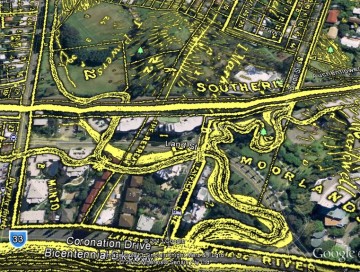

In fact, much of this land remains undeveloped today. In the image below, I have overlaid McKellar’s map onto the present-day landscape in Google Earth. The section of the stream closest to the river, along with the branch that heads towards the croquet club, flowed through what is now Moorlands Park (Moorlands being the name of the residence that John Markwell built where the Wesley Hospital is today).

Langsville Creek as depicted on McKellar’s 1895 map, overlaid onto the modern landscape in Google Earth.

Another branch of the stream flowed alongside what is now Land Street and past the Regatta Hotel. The surrounding land has now been populated with residential units. Yet another branch forked off towards the railway line, before reaching the open space of Toowong Memorial Park.

The pond constructed in the grounds of Auchenflower House, 1885. (State Library of Queensland, Neg. no. 150992)

You may also have noticed the doughnut-shaped pond next to the croquet club. This was part of the gardens of Auchenflower House, the residence of Sir Thomas McIlwraith, who was Queensland’s Premier from 1879 to 1893. As you can see in the photograph, and from the exaggerated terrain in Google Earth, this pond was constructed on a slope just above the creek. The stream itself is tantalisingly out of view in this photograph, but its course can be inferred from the row of trees along the fenceline, the dense vegetation on the other side of the railway line, and (more obviously) by the railway bridge in the middle of the frame.

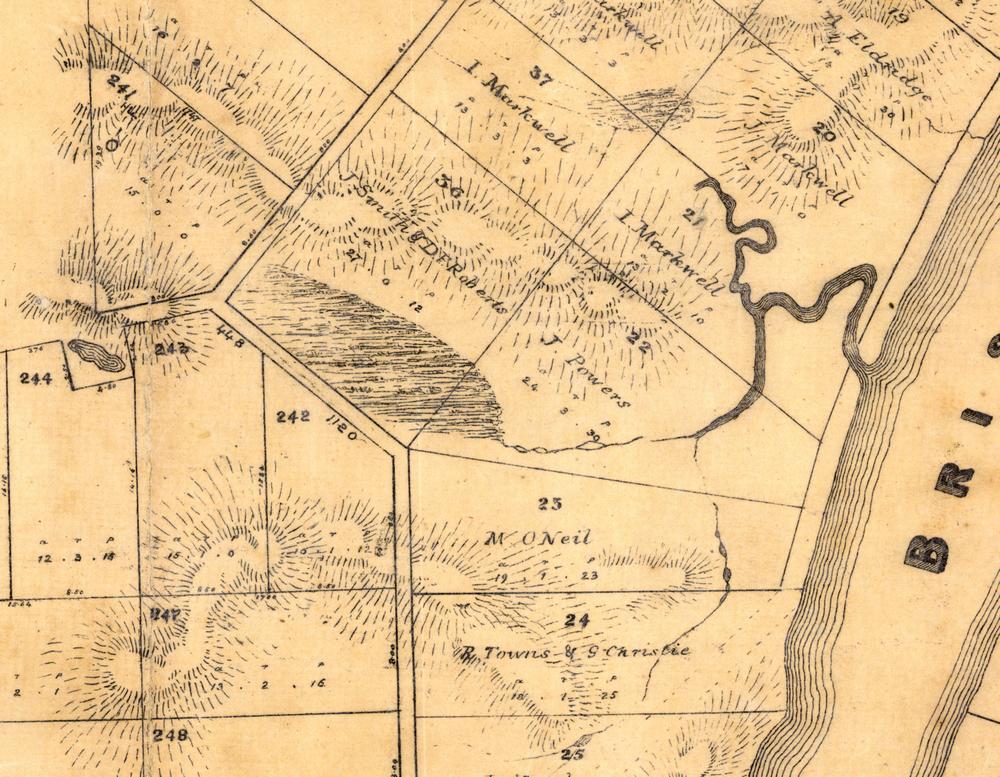

Langsville Creek also appears prominently on a map from 1859 of Portions 203 to 257 in the Parish of Enoggera, shown below along with its Google Earth overlay. The basic shape of the creek is the same as on McKellar’s map, but there are some interesting differences. The branch heading towards the Regatta is drawn more tentatively, looking more like a delicate chain of ponds than a permanent channel. The branch flowing through Toowong Memorial Park opens out into a large swamp that reaches all the way to Milton Road. And while the doughnut-shaped pond is absent (it was probably not built until the 1880s), there is a small swampy area visible where the croquet lawn is today.

There is also a subtle difference in the path that the stream takes through Toowong Memorial Park. In the 1859 map the stream arcs gently across Land Street and towards the park, while in the 1895 map it bends sharply and flows parallel with the railway line before turning again to align with Sylvan Road. This suggests that the channel was re-routed, presumably to make room for a building or other development — but I have no idea what this might have been, and the possibility remains that the course of the channel changed naturally over the years.

Oxley’s altercation

Langsville Creek makes a brief appearance in one of the earliest written records of the Brisbane area: John Oxley’s field book from his expedition up the Brisbane River in September 1824. Oxley, who was then the Surveyor General of New South Wales, had discovered and named the Brisbane River about a year earlier. He had returned to Moreton Bay to assist Lieutenant Henry Miller in establishing a new convict settlement and to explore the river in the company of the Colonial botanist Allan Cunningham and Lieutenant Butler of the 40th Regiment.

Oxley’s party set off on Thursday, September 16th and by Tuesday the 21st had taken the boats as far upstream as the Mount Crosby area, at which point the boats could go no further (the stream was low because the area was in drought). After exploring the area on foot with Cunningham, Oxley headed back down the river on Saturday the 25th.

On the evening of Monday the 27th, Oxley’s party came to what he described as the ‘Crescent Reach’ — what we know as the Toowong and Milton reach of the river. Here Oxley expected to find fresh water, and so intended to camp for the night. In choosing a campsite, he was careful to keep some distance between his party and the local Aborigines, having already encountered trouble with them earlier in his journey:

We saw at the commencement of the reach on the left bank a very large assemblage of natives in the same spot as we saw them last year. We landed about half-mile below this encampment on the same side of the river, there being a small creek between us, which I hoped would prevent them visiting us.1

The distance between the mouth of Langsville Creek and the top of the Toowong Reach is indeed half a mile, so there is little doubt that this is the creek that Oxley mentioned. In any case, camping there did nothing to prevent conflict with the natives. While Oxley and Lieutenant Butler went in search of fresh water (which they failed to find), a large contingent of the Aborigines descended upon the camp. Among them was one whom they recognised as having stolen Oxley’s hat at Breakfast Creek ten days earlier. After hurling a piece of wood at Oxley (and missing), the man prepared to throw a stone at Lieutenant Butler, who fired his gun and struck the man on his left arm and side. This put an immediate end to the altercation, but howls from the camp upstream were heard through much of the night.

The next morning Oxley’s crew made a quiet exit before landing just downstream at Western Creek to look again for fresh water. This time, he found it.

Langsville’s last gasp

So, that was the creek that was. But sometime after 1895, Langsville Creek met its demise. Exactly when, I do not yet know. But let’s see what we can learn by looking at the 1946 aerial photos, which, as far as I know, are the earliest such photos of Brisbane. You can explore them via the City Council’s PDOnline Interactive Mapping page, but here we’ll be looking at them with Google Earth.

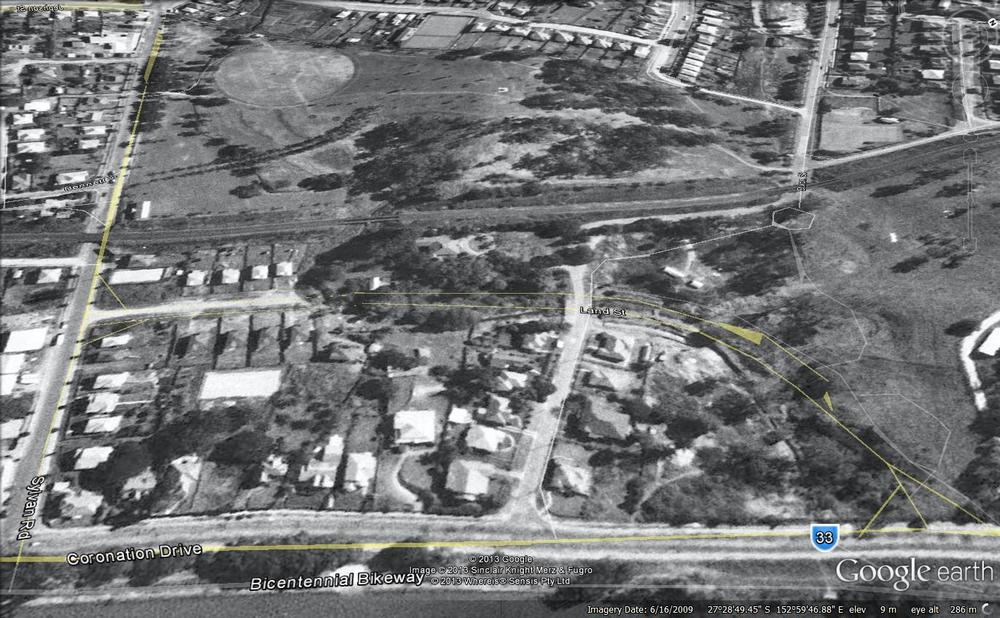

The first image below shows roughly the same area as those above. But the branching, meandering stream depicted in the old maps is all but gone. The hairpin bend near where the creek met the river has been replaced by an open concrete drain tracing roughly the same arc as Land Street does today. (To see Land Street and the rest of the modern landscape, just hover your cursor over the image.) The branch that meandered towards the croquet club has already been covered by parkland.

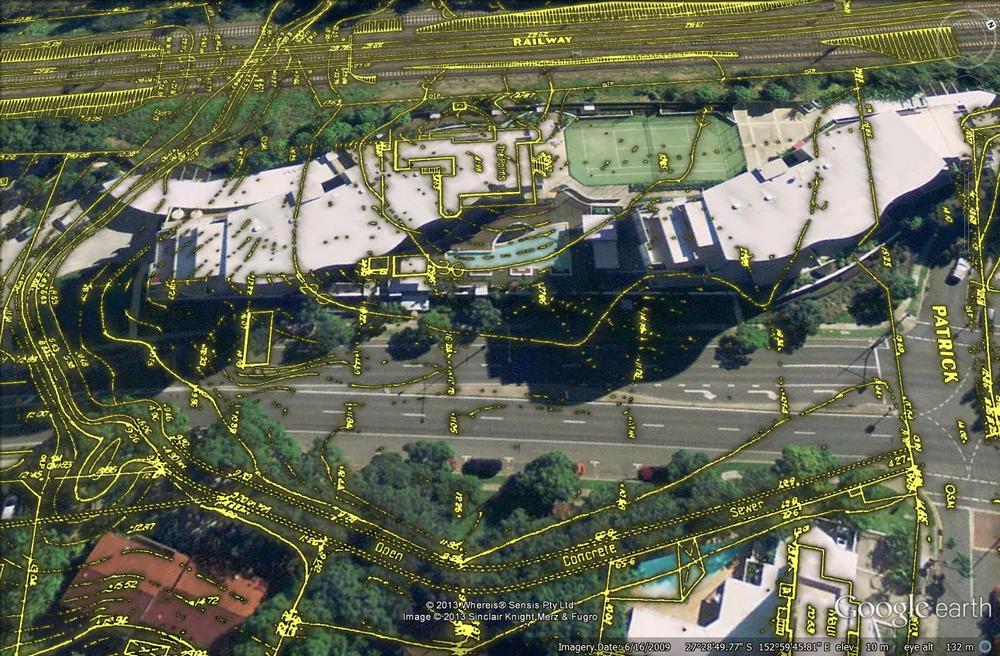

On the other side of Patrick Lane there is something interesting: an open drain that follows the same curving path of the old creek. It is surrounded by trees, and it stands stubbornly in the way of the short dirt track that will eventually become Land Street (an intriguing name, given that it was built over the creek). By the time it reaches the railway line, the drain doesn’t even appear to be lined. We appear to have have caught this part of the creek mid-way through its demise. The image below shows the same area up close, overlaid with the Water Supply and Sewerage Board’s detail plan from 1935.2 The alignment is not perfect, but you can see where the “open concrete sewer” gives way to the contours of the streambed.

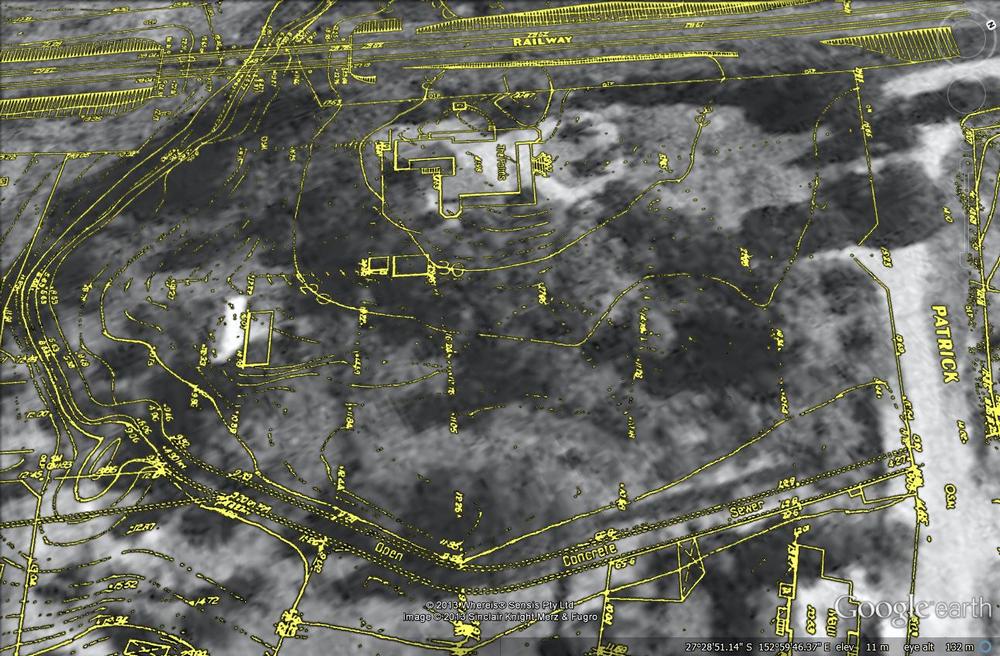

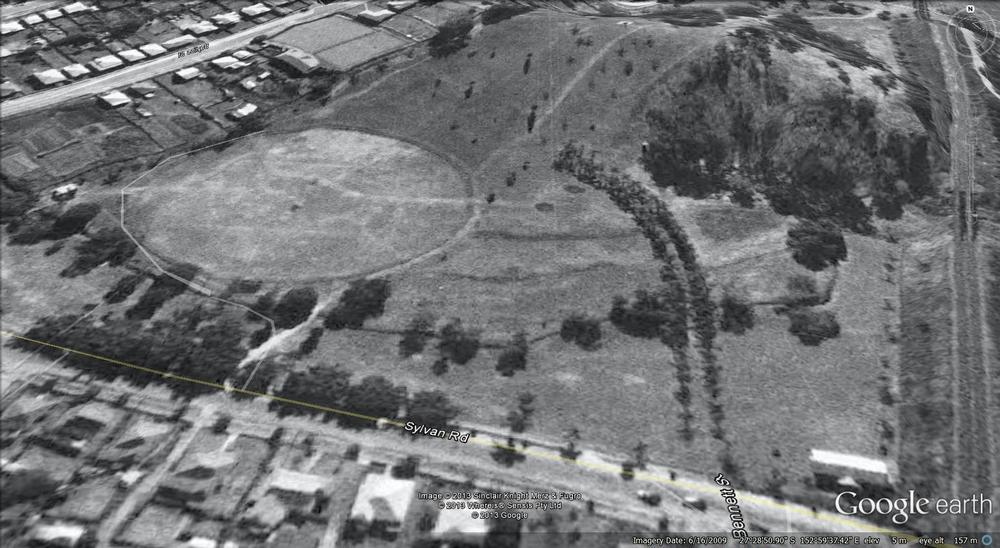

On the other side of the railway line is Toowong Memorial Park, shown in the image below. Here we can see a narrow, bare channel, dotted sparsely with trees, stretching from the railway bridge across the length of the park. It follows more or less the same path as the original stream depicted in the maps above. This is what the lower reaches of Langsville Creek had been reduced to by 1946.

Actually there is one more bit of the stream that we can see in the 1946 images. In the neighbouring block at the top of the park, the creek flowed through what look to be some market gardens. These gardens are right in the middle the large swampy area that appears in the 1859 map shown earlier.

Beginning from the end

The way I have described Langsville Creek in this post is, in an important sense, back-to-front. I have started from the bottom end of the stream and talked as if it flowed inland from the river. That’s certainly how it looks in the old maps (especially McKellar’s), and to a certain extent I suspect that this is how the creek actually worked. In the lowest, flattest reaches of the creek, there was probably more water flowing in from the river than flowing out from the creek (unless there had been heavy rain in the catchment, of course). If the river here was tidal (which it probably was in 1895, but may not have been in 18593), this effect would have been even more noticeable.

But to talk of a creek this way is to disguise its true origins. The river is where a creek ends, not where it begins. So, if this is the end of Langsville Creek, where does it begin, and what lies upstream?

Tune in to the next installment (whenever that may be) to find out!

Notes:

- I have quoted Olxey’s field book from the transcription in J.G. Steele’s The Explorers of the Moreton Bay District 1770-1830 (University of Queensland Press, 1972), which is much easier than deciphering Oxley’s handwriting from the digital reproduction available on the State Library of New South Wales website. ↩

- Dating these plans can be difficult, as many of them were revised some years after they were initially drafted, and some we were published on a different date yet again. This particular plan (no. 838) is hand-dated 1935, but according to an index kept by the Brisbane Archives it was drafted in 1927, revised in 1931 and published in 1935. The same index says that the neighbouring plan (no. 839), which shows the open concrete drain from Patrick Lane to the river, was revised in 1942. ↩

- In 1896, Toowong Councillor A.C. Gregory led a deputation to the Colonial Secretary in to request Government assistance in addressing the nuisance at Red Jacket Swamp (now Gregory Park). In outlining a proposed drain between the swamp and the river, Gregory explained that “the tidal waters came into the swamp, and the salt water killed the vegetation, and so caused it to fester and give off unhealthy odours”. (The Brisbane Courier, 24 July 1896, p7.) But this all happened after the tidal dynamics of river had been substantially changed by dredging and other modifications, which begun in the 1860s. Prior to these modifications, the tides would not have reached as far up the river. ↩

Another great read and thanks for the info, i am always riding my bike through these areas and have noticed the drains and land contours.I have also noticed near langsville park but closer to Coronation drive some old fencing that may have been part of the old bridge ?

Hmm, I haven’t seen the fencing but will look out for it next time I’m there. You can still see bits of the old Dunmore Bridge under Coronation Drive at the mouth of Western Creek (or you could when it was not a construction site). A remnant of Langsville Bridge would be interesting.

Pingback: Uncovering Langsville Creek, Part 2 – The catchment | There once was a creek . . .

Pingback: Bottles and cans: an adventure in suburban archaeology | There once was a creek . . .

Pingback: Langsville Creek, Part 3 – The Headwaters | There once was a creek . . .

This is a fascinating and very beautiful work that you have conducted. The importance and value of people like you cannot be underestimated.