This is the second in a series of posts about Langsville Creek, which was Western Creek’s upstream neighbour on the Toowong/Milton Reach. You may want to check out Part 1 and Part 3 of the series.

The whole iceberg

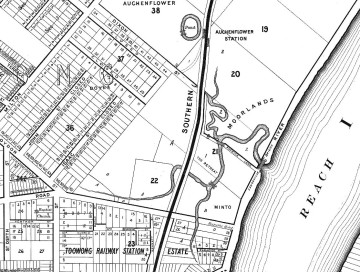

If you look at the Milton Reach of the river on any of the old maps of Brisbane, such as the one drawn by A.R. McKellar in 1895 (shown to the right), you will notice a creek with several winding branches that meets the river at Patrick’s Lane. This was known as Langsville Creek. As we saw in Part 1 of Uncovering Langsville Creek, the creek as it was depicted on the old maps is now gone. A few drain openings are about the only physical reminders left of what must have once been a prominent part of the landscape.

But there must have been more to Langsville Creek than just the meandering branches shown on the early maps. Each of these branches must have had an origin somewhere further upstream. With one or two exceptions, the early maps show nothing of those upstream parts of the creek. Our understanding of Langsville Creek will remain very superficial, however, if we do not look further than what we can see on the maps. It would be like trying to understand an iceberg while ignoring everything under the water. If we want to uncover Langsville Creek and its legacy in today’s landscape, we need to look further upstream: we need to see the whole iceberg.

A tour of the catchment

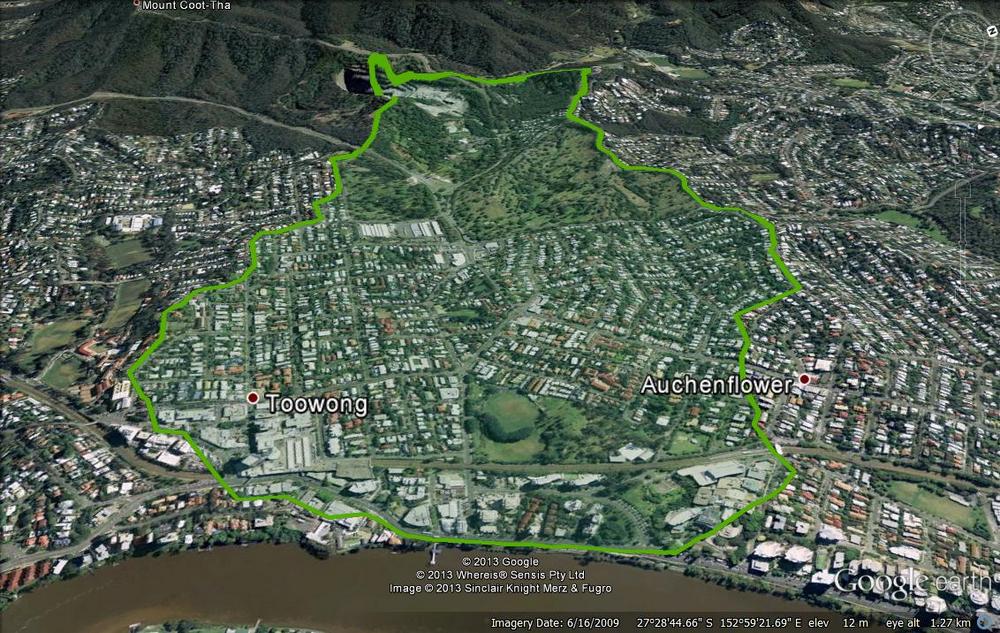

One way to trace the origins of Langsville Creek would be to start where streams on the maps end and follow each of the branches upstream, using the shape of the terrain to guide us. But instead we are going to step back, zoom out, and identify the whole area of land that drained into Langsville Creek. In other words, we are going to identify the creek’s catchment.

Determining a catchment area is fairly straightforward. There’s little more to it than tracing a line along the highest ridges that surround a stream. To save yourself some legwork, you might get hold of a map showing contour lines and trace the ridges that way. But these days we can make a computer do all the work by feeding it a dataset of the relevant terrain (a digital elevation model, or DEM). This is the method I used to produce the outline of Langsville Creek’s catchment that you see below. It’s not perfect, but for our purposes it is good enough. If you have Google Earth installed, then you can explore the catchment for yourself by downloading this file.

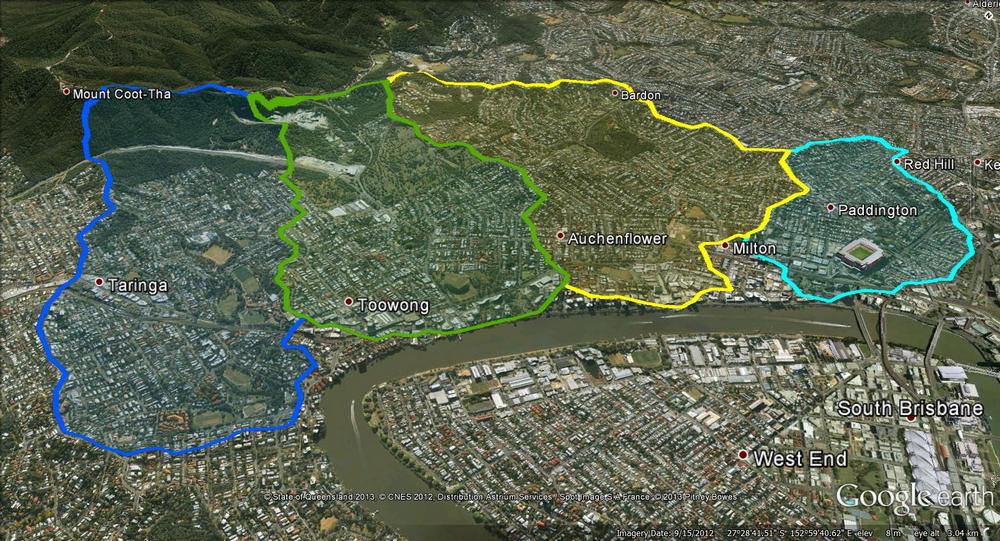

The Langsville Creek catchment stretches from the river all the way up to the quarry at the base of Mount Coot-tha. It backs onto the Ithaca Creek catchment and sits snugly between two other catchments that flow into the Toowong/Milton Reach of the Brisbane River: Western Creek and Toowong Creek. These are shown in the image below, along with the catchment of Boundary Creek, which lies closest to the CBD. You can read more about the catchments of the ‘Crescent Reach’ (as John Oxley called this part of the river) in this post.

The catchments of the Crescent Reach. From left to right: Toowong Creek, Langsville Creek, Western Creek and Boundary Creek.

From the treetops – the northern boundary

Let’s look first at the northern boundary of the catchment, which is also part of the boundary of the Western Creek catchment (note that the Google Earth images above have been rotated, so you’ll have to check the compass in the upper-right corner of the image to see which way north is). We should really start at the highest point, which would be Stuartholme School, but since that’s private property we’ll start at the top of Birdwood Terrace instead. There is a small, fairly recently built housing estate up here called ‘Treetops on Birdwood’. If you are lucky enough to live here, you most likely have a splendid view of much of the catchment.

The northern boundary follows Birdwood Terrace past the Toowong Cemetery and as far as Slade Lane, where it continues along the ridge down through Auchenflower towards the Wesley Hospital. Along the way it cuts through Milton Road — or rather, Milton Road has been cut through it. A large chunk of the hill has been chiseled out here to flatten out the road, and the result is that you can see the catchment boundary in cross-section.

A catchment in cross-section. This panorama of Milton Road shows the ridge separating the Western and Langsville creek catchments. (The road here is not actually curved — that is just an artefact of the panorama.)

Steps on the footpath along Milton Road. These steps follow the original hill, which has been cut down along the roadway.

On both sides of the road, the original footpaths are still intact, running along what would once have been the fronts of the houses. These two footpaths are rather enchanting spaces. They are like little overgrown time-capsules. You could easily miss them even as a pedestrian, since there are also lower, flatter footpaths immediately beside the road.

Through the hillside – the southern boundary

Starting again from the top of the catchment, let’s now follow the southern boundary, which is shared with the catchment of Toowong Creek. It starts somewhere along Scenic Drive and then cuts straight through the quarry, though probably not quite along the path shown in the Google Earth images above. The pit of the quarry is a man-made catchment or ‘sink’ unto itself, and the boundary of the Langsville Creek catchment must run somewhere along the northern edge of the pit (just out of view in the right-hand side of the photo below).

The southern boundary then follows a ridge through the botanical gardens and across the freeway. Despite the large chunk that has been carved out of this ridge to accommodate the freeway, the road here still rises and falls (try riding along the bike track if you don’t believe me!), thus leaving the catchment boundary intact.

View of the South-Western Freeway from the edge of the Botanical Gardens. The hill that has been cut down is the boundary of the Langsville and Toowong creek catchments.

From the freeway, the ridge continues above Anzac Park and along Dean Street and Sherwood Road, then through the top of Brisbane Boys College, and finally towards the river via High Street.

The power of three

The total area of the Langsville Creek catchment is about 3.3 km2. This is by no means a large catchment — it is not even as big as the catchments of Western Creek and Toowong Creek, which each cover about 4 km2. But three square kilometres of land is ample space for water to collect and coalesce into sizable streams.

We could take this analysis further and identify the subcatchments within which these streams would have formed before they converged upon the main stream of the creek. But these subcatchments will quickly become evident once we start tracing the streams themselves, which we will do in the next installment of Uncovering Langsville Creek.

In the meantime, you might like to think about the three branches of the stream that are depicted on McKellar’s map and others from the 19th century. Might these three branches suggest three distinct subcatchments, which only meet each other just before Langsville Creek itself meets the river? And if so, which was the bigger stream — the one we might call the trunk stream of Langsville Creek? If you know the area well, then you might already be able to make an educated guess. If not, stay tuned for future installments, and we’ll make some educated guesses together.

Interesting post Angus. There is a section on the Milton Road “cut” of the watershed ridge in Prof. Pearn’s Auchenflower book. It was made for the extension of the electric tramway to Toowong in 1904, the “deepest tramway cutting in Brisbane”. The old rattlers couldn’t ascend many of the steep hills of Northern Brisbane. The old paths over the top are indeed hidden, I lived just down the road for a year before I found them.

Pingback: Langsville Creek, Part 3 – The Headwaters | There once was a creek . . .

Pingback: Uncovering Langsville Creek — Part 1 | There once was a creek . . .

That cutting photo is just outside the house my grandparents used to live in. I believe the cutting was widened during the 60s, as a kid I never understood why they referred to the front yard when there was about 2 meters of it before Milton Road.

Bitcoin Investment Deutschland: http://cort.as/-PSJw?&wojlf=URPWWfA7ahgcY