There’s nothing like a change in surroundings to cast your normal environment — that familiar place you call ‘home’ — in a new light. The closer you are to something, the easier it is to forget what makes it special or distinctive.

For me, home has always been Brisbane’s western suburbs. I’ve lived in Bardon, The Gap, Toowong and, most recently, Roaslie (which nowadays is just a part of Paddington). But a few months ago I ventured outside my native habitat, moving across the river to the southside, landing in a sort of semi-rural-industrial outpost called Rocklea.

Like Rosalie, Rocklea is built on a floodplain, and to that extent probably should never have been built at all. But that’s about where the similarities end. It’s not just that you won’t see any cows or two-train semi-trailors in Rosalie, or that the local cuisine there gets more exotic than meat pies.1 For me, the most striking difference between my new environment and my old one is the topography. I’m used to living among hills. In Brisbane’s western suburbs — in Paddington, Bardon, Ashgrove and Toowong, for example — there are ridges that you can follow all the way up to Mount Coot-tha. In those parts of town, you live either on a hill or at the bottom of one.

Not so in Rocklea. If I look to the west from here, the first big hill I can see is the southern tip of the D’Aguilar Range. To the north-west it is Mount Coot-tha and the Taylor Range. The CBD lies nearly 8km to the north, but from here you can generally get city views by climbing a tree.2 To the east it’s easy riding until you hit Toohey Mountain and then Mount Gravatt. To the south, on a clear day you can see just about forever, and leading you most of the way there is the great floodplain of Oxley Creek.

There’s nothing unusual about this sort of terrain. In a land as old and dormant as Australia, flatness is the norm and mountains the exception. Mount Coot-tha, Mount Gravatt, Mount Toohey and other such peaks around Brisbane are with us today only because they are made of sterner stuff (namely granite) than the land around them. They have stood firm while the rest of the landscape has eroded away.

But my geographic sensibilities were forged in the hills, and so the hills remain my normality. I only tend to notice them when they are not there.

Mountainless Melbourne

My move from Brisbane’s hilly west to its much flatter southside delivered a mild jolt to my geographic sensibilities. But another recent adventure left me with a full-blown case of topography shock. This adventure took place much further south than Rocklea: it was a week’s holiday in Melbourne.

Visiting with no fixed itinerary, I spent much of the week just roaming the streets of Melbourne’s CBD and inner suburbs, stopping every few blocks at whichever pizzeria, souvlaki bar, kebab stand, bakery, dumpling house or cafe most took my fancy. Melbourne is tailor-made for this kind of pedestrian indulgence. Its city streets and suburban precincts are packed tightly with shopfronts, the procession of which is interrupted only by entrances to smaller lanes and alleys which lead you to even more eateries, street art and other unexpected treasures. For the wanderer’s convenience, all of this is laid out neatly on straight roads, in regular blocks, on flat ground.

If I had to choose one word to describe Melbourne’s culture, it would be ‘vibrant’. Wherever you turn, there seems to be something happening, something to see, something to do, and especially something to eat. But the city’s topography is the quite opposite. It is completely uneventful, and in all directions looks exactly the same.

For someone so used to Brisbane’s hills, the flatness of Melbourne is rather startling. I found it almost unnerving. My impulse to look for high ground from which to see the lie of the land was continually frustrated. No one point seemed much higher than any other — at least, not until I adjusted my sense of proportions. Like objects coming into focus in a darkened room, Melbourne’s subtle slopes became more apparent once I lowered my gaze.

The view from Flagstaff Gardens towards Melbourne’s harbour. (Flickr: Charlievdb)

Wandering northwards one evening along King Street, I came across a place called Flagstaff Gardens. As a sign in the corner of the park explains, the site got its name from a flagstaff that was erected here in 1840 as a means of signalling to the boats in Port Philip Bay. From this ‘hilly vantage point’ (the sign’s description, not mine), the early settlers could see the whole colony.3 You can still see the harbour off to the south-west, but the rest of the view is blocked by buildings and trees.

I suppose you could think of Flagstaff Gardens as Melbourne’s equivalent of Brisbane’s observatory (the old windmill) on Spring Hill. But on Spring Hill you don’t need a sign to tell you that you’ve got a good view. Had I not read the sign inviting me to ‘climb the hill’ at Flagstaff Gardens, I would probably not have even noticed the site’s privileged position, let alone suspected its historical significance. Melbourne must be flat indeed if this is the biggest hill in town.

To be fair, there was one hill near the city centre that I noticed even without the help of a sign. It is on the south side of the Yarra, and is big enough that you might even break a sweat walking up it. Indeed, it is big enough that the makers of Melbourne, with so much flat ground to choose from nearby, didn’t bother to build on it: they put the Royal Botanical Gardens there instead.

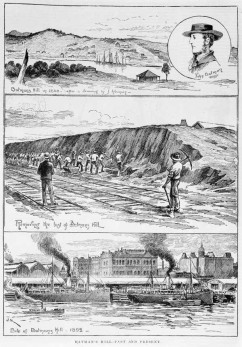

The removal of Batman’s Hill, as depicted in an engraving from 1892. (State Library of Victoria)

There was once another hill in Melbourne, perhaps even larger than the one in the Botanical Gardens. Batman’s Hill — so named because it was where John Batman, one of the city’s founders, built his home in 1836 — marked the natural western boundary of the city when the first surveyor’s pegs were laid down. It was also the point of origin (or datum, to use the surveying term) from which the city was first surveyed. After Batman died in 1839, the hill served as a grandstand for Melbourne’s first horse race, and as the site of Melbourne’s first cricket match. It also served more mundane functions, playing host to navigation beacons and a hospital.

In a city that today boasts the largest cricket arena in the country, and that grinds to a giddy halt once a year on account of a horse race, Batman’s Hill should have become sacred ground on account of its sporting heritage alone. Yet neither that nor the site’s geographical and colonial significance must have mattered very much when the gold rush was in full swing. Once the railway got going, Batman’s hill become an inconvenience, and by 1866 it had been demolished to make way for the expanding Spencer Street Station. The message to any other hills in Melbourne was clear: keep a low profile, or be cut down to size.

Eureka!

Melbourne’s Eureka Tower (Flickr: thewamphyri)

Having found Melbourne’s version of the Spring Hill observatory, I began to look for Melbourne’s Mount Coot-tha. Where could one go, I wondered, to take in a view of the whole city at once? Eventually I had to accept that the only answer was the Eureka Tower. Although not a mountain, the Eureka Tower is as tall as one. Standing 297m above the city, it is in fact ten metres higher than Mount Coot-tha. The view from the Skydeck (which at 285m is two metres lower than the lookout at Mount Coot-tha) confirms spectacularly the impression gained by walking the streets below. Stretching for miles in every direction (except south, where you run into the ocean) is a vast, flat plain of human settlement. Complementing the flatness of the landscape is the low, almost uniform profile of the built environment, which (ignoring the skyscrapers of the CBD) is punctuated only by a few old factory chimney towers and the public housing buildings from the 1960s that look like giant cardboard boxes. Way off in the distance, barely discernible in the haze, are the mountains of the Dandenong, Yarra, Macedon and Brisbane ranges. So these are Melbourne’s mountains.

The view of Melbourne from the observation deck on the 88th floor of the Eureka Tower. (Flickr: pasukaru76)

Seen from this height, the city seems to sprawl indefinitely: you can’t really tell where it ends and the mountains begin. But if you look closely you can see that it is not without structure. Imprinted into this vast urban fabric is another of Melbourne’s defining features: the grid.

A city full of squares

If Melbourne is the hipster capital of Australia, then it must be hip to be square. Melburnians (for some reason they tend not to call themselves Melbournians) probably take the grid for granted. But to a Brisbanite (or at least to this one), the grid is just as startling as the featureless terrain in which it is set.

Actually, there are two grids. The first is the CBD, which takes the form of a rectangle outlined by Flinders Street, Spring Street, Spencer Street and La Trobe Street. Cutting through this rectangle are six main streets running from Flinders Street to Latrobe Street, and three running from Spencer Street to Spring Street. All the streets are evenly spaced, yielding 32 perfectly square blocks.

Melbourne’s central business district is an augmented version of the grid designed by Robert Hoddle in 1837. View Larger Map

The grid of Melbourne’s CBD even has a name — the Hoddle Grid, after the surveyor, Robert Hoddle. The grid that Hoddle drew up in 1837 was one row short of the grid of today, extending only as far north as Lonsdale Street. It was exactly one mile wide and half a mile tall, and each block was exactly 10 chains (201 metres) square. The generously wide streets all span 30m, or one and a half chains. The grid’s geometric purity is broken only by a rare concession to the landscape on which it sits: it is rotated about 20 degrees anti-clockwise from true north so that it aligns with the Yarra River.

The town of Melbourne as surveyed by Robert Hoddle in 1837 (more information).

If you look closely at Melbourne’s CBD (try zooming in within the Google Maps frame above), you will see that the 32 blocks described earlier comprise just one layer of the grid. Each of the main streets running from east to west has a ‘Little’ version of itself (Little Lonsdale Street, Little Bourke Street, Little Collins Street and Flinders Lane) that divides each block into two smaller units. Running off these streets is an even finer capillary network of lanes and alleys.

Grids within grids! Already Melbourne is starting to resemble a piece of fractal geometry, but this is only the half of it. Stepping back again — back to about where we were in the Skydeck — you will see that the CBD is itself just a little grid at the centre of a much larger matrix: that of Melbourne’s suburbs.

The grid of Melbourne’s suburbs covers an area about 40km wide. View Larger Map

Melbourne’s suburban grid is rotated about 28 degrees clockwise from the Hoddle Grid, or eight degrees from true north. Whereas the Hoddle Grid was aligned with the Yarra River, the suburban grid doesn’t appear to align with anything. This may seem strange: with no obvious constraints, surely Hoddle and his surveying buddies would have chosen a perfect north-south, east-west alignment for the city. In fact, they did just this, except they aligned the grid with magnetic north (the direction in which a compass points — that is, towards the magnetic north pole) rather than true north (the direction towards the geographic north pole). Magnetic north differs depending on where you are, and it changes over time. In Melbourne today, magnetic north is about about 11 degrees east of true north; a hundred years ago it was closer to eight degrees east, bringing it into perfect alignment with the axes of Melbourne’s suburban grid.4

Though there are a few pockets of resistance, principally around the Yarra and Maribyrnong rivers, this grid rules across nearly the entire city, from as far south as Frankston, as far east as Vermont, as far north as Broadmeadows, and as far west as Deer Park. That’s nearly 40km east to west and 50km north to south. Because the grid is so large, and the land so flat, there are places where you can stand in the middle of a street (easy to do in Melbourne, thanks to the tramlines) and see the street disappear in both directions into the horizon. There are not many places in Brisbane where you can do this. Nearly every street in Brisbane will disappear over a hill or round a bend before the horizon can even get a whiff of it.

It is as if the whole city of Melbourne was dreamed up in some engineer’s mind and transferred onto the landscape without the fuss of having to check what might get in the way. The reality would have been a bit more complicated than this, but the point is that the city could not (or at least would not) have been built this way had the landscape not been so accommodatingly flat. Had there been a few more hills and waterways to disrupt the grid, Melbourne’s streets would have taken on a different geometry altogether. Something more like Brisbane’s, for example.

Constrained by a river, creeks and hills, Brisbane’s streets rarely conform to a grid for more than a few blocks. View Larger Map

The difference between this unruly plate of spaghetti and Melbourne’s waffle-like lattice hardly needs any commentary, but we’ll take a quick look anyhow. To be sure, in Brisbane there are little bits of grid here and there. In fact there are lots of them, but you’ll be lucky to find one that covers more than a few blocks. Furthermore, nearly every one of these ‘gridlets’ has a different alignment to the next, so there is no sense of a broader structure or master plan uniting them.

The biggest grid-like structure that I can see in Brisbane (at least by cruising on Google Maps) is the network of main roads stretching from Grange to Bracken Ridge, taking in suburbs such as Chermside and Zillmere along the way. With the notable exception of Gympie Road, most of the main roads in this area follow a single grid alignment. The grid pattern is very weak, however, when you look at the network of smaller streets attached to these main roads. In the area around Holland Park West on the southside, the same thing can be observed.

Except in a few patches like these, Brisbane’s landscape is just not hospitable to straight lines. The city’s river, its creeks and its hills all conspire to ensure that no road can be straight for very long, at least not without becoming the second-best option. Within these geographical barriers and constraints, the roads of Brisbane (the main ones, anyway) follow paths of least resistance, hugging the natural contours of ridges and watercourses. In doing so, they trace out the messy signature of Brisbane’s geography.

There are exceptions, of course. Sometimes, the advantages of a shorter trip outweigh the inconvenience of a steep hill, especially if your are driving a car rather than riding a bicycle, or for that matter, driving an electric tram. Yes, Brisbane too had a tram network once upon a time. When the tramlines were laid in Brisbane’s suburbs, many hills had to be cut down to provide a gentler gradient for the trams. The deepest of these hill cuttings was along Milton Road, at the ridge separating the Western Creek and Langsville Creek catchments. It might not be Batman’s Hill, but from the top of the old footpath, this cutting is quite a sight to behold.

Many parts of Brisbane are too steep for trams, but where there is a will, there is a way. This road cutting on Milton Road was reputedly the largest in Brisbane.

The landscape’s legacy

Before finishing up, I need to confess that my earlier account of Melbourne was something of a caricature: I committed a few simplifications and omissions to make a point. While marvelling at the size and completeness of Melbourne’s suburban grid, I neglected to mention that a few of the most prominent roads deviate from it completely, curving and winding much like the roads in Brisbane. These are Melbourne’s freeways, visible on the Google Map shown earlier as thick orange lines. Some of them, especially the Eastern Freeway, Monash Freeway, and the Calder Freeway, follow watercourses, which aside from being the flattest corridors available are also typically the least developed, making them perfect for a major arterial road. The Princes Freeway does the opposite, crossing several waterways along a direct route to Geelong. It can do this, I gather, because the land it traverses is close to the coast and therefore mostly flat.

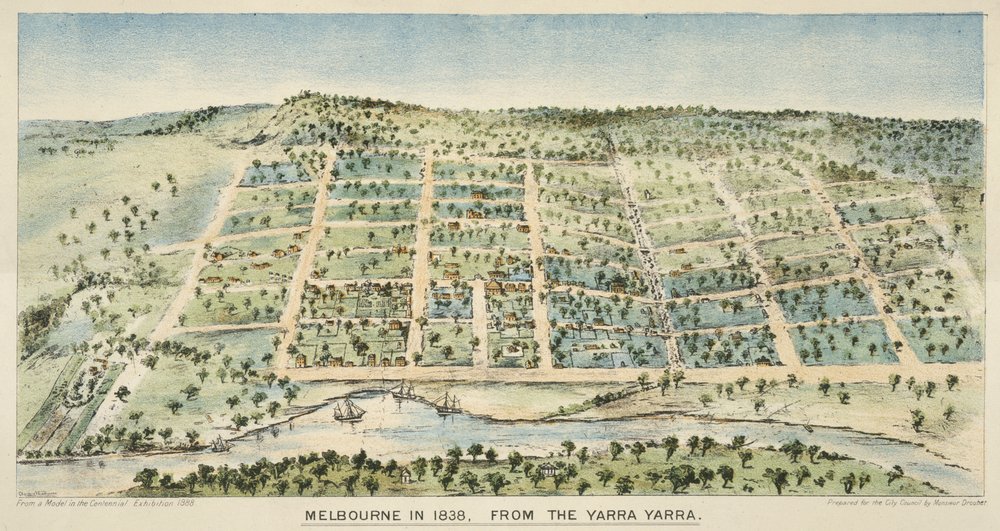

It would also be simplistic to suggest that Hoddle’s grid, in all of its mathematical purity, ignored the landscape completely. As well as aligning with the Yarra River, the grid incorporates a gentle valley. At the bottom of the valley today is Elizabeth Street, but in Hoddle’s day there was a creek. If you look closely at the watercolour painting below depicting Melbourne in 1838, you’ll see that Elizabeth Street at that time was not a street at all, but a drain, flowing uncovered all the way to the Yarra. Even when it become a street, it never ceased to be a watercourse. One account of a flash flood in 1891 tells of a ‘great tidal wave’ rolling down the street and sweeping people away.

Melbourne in 1838, painted (apparently from a model) by Clarence Woodhouse (1852-1931). Flagstaff Hill (possibly exaggerated) is in the upper left of the picture, while Batman’s Hill (cut down in 1866) is in the lower left. (State Library of Victoria)

Examples like these demonstrate that even within a geography as placid as that of Melbourne’s, you can’t keep the landscape down: in one way or another, it eventually will make itself known. Often, as in the case of floods, it will do so at great cost and inconvenience to the people living in it. But on other occasions it gets resurrected more willingly. Whether recreated physically or just invoked symbolically, the landscape and its natural features are often clung to as a source of local identity, even in a city as culturally proud as Melbourne.

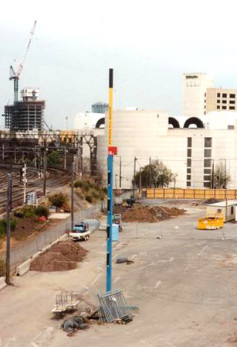

The Batman’s Hill Marker near Spencer Street Station in 2003. (Coburg Historical Society, via Picture Victoria)

Take Batman’s Hill, for example. Although its slopes have long been absent from the landscape, its name is still on the map, and has even found its way into the phone book. It lives on, for instance, in the Batman’s Hill Hotel, which opened in the 1920s, and in a new precinct currently being developed at Docklands.5 The hill’s height and position have been commemorated by an 18m high surveying marker close to the original datum of Hoddle’s survey.6 Nearby, the Collins Street Bridge — which runs from Spencer Street Station to Docklands Park, straight through where the hill once stood — traces the shape of the hill’s original profile. In a city virtually devoid of hills, this one seems in no danger of being forgotten.

I certainly hadn’t forgotten the hills of my hometown. I knew that when I returned they would be looming higher than ever after my week in flatland. As it happened, my flight home was a late one, so through the tiny window I couldn’t even make out the silhouette of the Taylor Range. As a consolation I caught a fantastic view of Brisbane’s CBD, with the river around it illuminated by the city lights. But I didn’t really feel at home until I stepped out of the plane and into the balmy Brisbane night, which was a full 13 degrees warmer and a great deal more humid than the frigid Melbourne evening I had left behind.

Not being one for shopping, I brought back little in the way of souvenirs, save for the extra kilograms sitting around my waist and the tap water from Tullamarine Airport sloshing around in my water bottle.7 The other thing I brought back was a mind bubbling with thoughts about how the topography of a place, and its natural history more broadly, can influence the experience of living there, not just through the immediate presence of hills and waterways but also through the way these things shape the built environment and cultural fabric. I’m glad to have gotten many of those thoughts out of my head and onto the page, but gladder still for the fresh perspective that they will cast on that familiar place I call home.

Notes:

- Actually I’m being unfair. Although you wouldn’t suspect it, the pie shop at Rocklea does a good Vietnamese pork roll. ↩

- If you draw a straight line from the Brisbane Markets to the CBD, you cross the river five times. Unless you cross Highgate Hill, it’s floodplain all the way. ↩

- This page features a photo of the view not quite from colonial days, but not long after, in 1866. ↩

- The Hoddle Grid Wiki mentions the shift in Melbourne’s magnetic north (otherwise known as magnetic declination). Using the map feature on magnetic-declination.com you can learn the declination for any location on Earth. ↩

- According to this article, there is a push for the hill’s heritage to feature prominently in the development. ↩

- Given that the marker was located in a construction site, I am not sure that it has been removed or incorporated into whatever has been built there. Confirmation from a Melbourne local would be appreciated! ↩

- Incidentally, I found the tap water in Melbourne to be much nicer than that in Brisbane. ↩

Granted, Melbourne’s urban sprawl is mostly on a featureless plain (the eastern suburbs the exception), but the CBD has many steep gradients that have warnings for wheelchair assistance and limited mobility individuals. In the west, all streets south of Bourke St. leading down to the Yarra are quite steep, plus the Elizabeth St./Swanston St. valley includes steep gradients west and east of it, especially Bourke St. west and Collins St. east. Thank you for mentioning the exceptional quality of Melbourne’s tap water. The best in the world, thanks to early catchment policies.

Hi Adam. Thanks for those corrections to my caricature of Melbourne’s topography. It is fair to say that I did not cover a great deal of territory in my visit. I will make a special point of visiting the hills next time.

Also, good to know that I wasn’t just imagining the lovely tap water!

Read the articles within this website quite a bit, going to take the plunge soon enough and get a

steam shower cabin, in all probability after the holidays

Here is my weblog – steam shower Review, http://www.youtube.com/Watch?V=zh5_zuux1nu,

That is similar to my own shower enclosure i actually got a hold of only recently,

extremely pleased with it for everyone found on the

fence on the subject of getting one, do it now,

you wont regret it

Here is my web-site :: Steam Shower Enclosures (http://Www.Youtube.Com)

Hi, I came across this interesting read whilst looking for an explanation for the north Brisbane grid alignment.