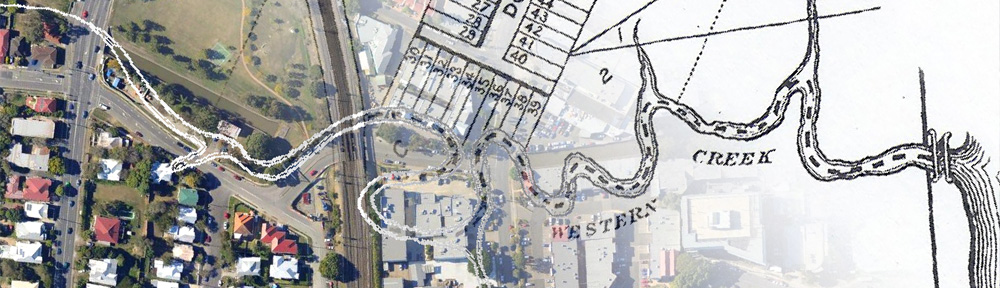

This is the fourth in a series of posts about Langsville Creek, which was Western Creek’s upstream neighbour on the Toowong/Milton Reach. Before reading this post, you may like to look at Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 of the series.

Previously, on Uncovering Langsville Creek . . .

The first three episodes of this little mini-series have unfolded much like a daytime soap: the plot has thickened, but not much has happened. Well, without giving too much away, this is the episode where things happen. It is the murder-mystery end-of-season thriller. Characters will die, secrets will be revealed, and lost worlds discovered. But first, a brief recap.

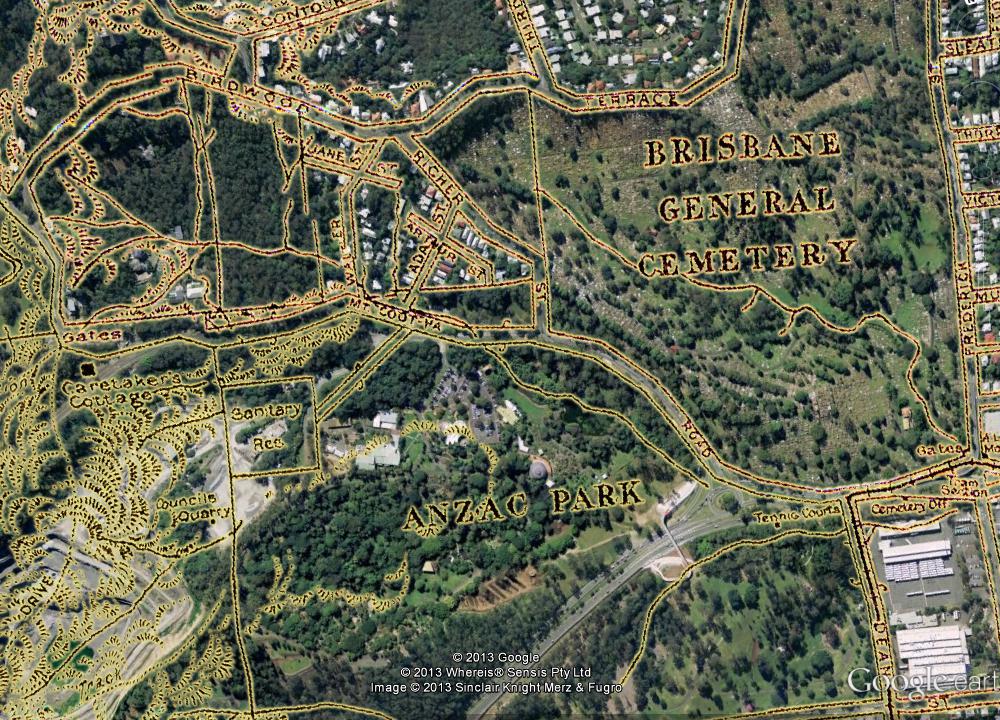

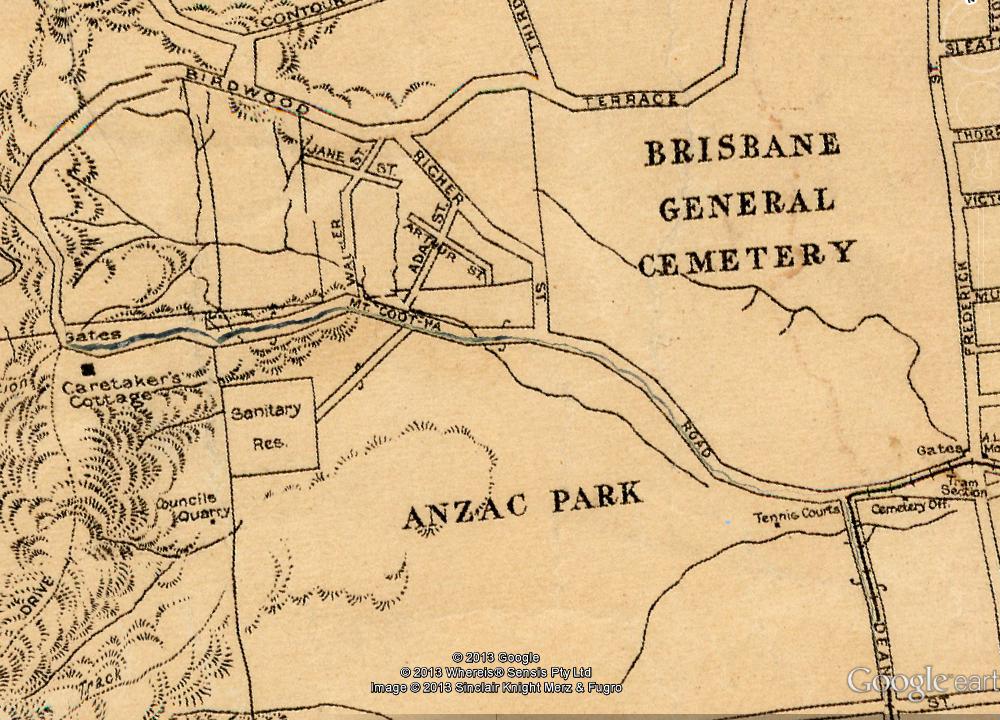

The previous episode introduced the map that you see below, which dates from 1929 and is the only one I have found that shows the upper reaches of Langsville Creek. We explored the stream that runs from the upper-left corner of the map into what is labelled as Anzac Park. Today, the area at the top-left is the Treetops on Birdwood estate, and the area labelled as Anzac Park is the Mount Coot-tha Botanic Gardens (hover your cursor over the image to see the modern landscape). In the slopes below Birdwood Terrace we found the headwaters of Langsville Creek more or less as they have always been — as gullies running through dry scrub. Immediately across the road, however, we found lush rainforest streams flowing into large lagoons, all part of the regulated water cycle of the botanic gardens.

Part of a map of Brisbane dating from 1929 (available online via Brisbane Images). The watercourses shown are the upper reaches of Langsville Creek. (Note that some distortions and artifacts emerged in preparing the map for Google Earth, most notably the giant crack running along Mount Coot-tha Road.)

At the end of the Western Freeway, where the entrance to the Legacy Way tunnel is still being built, the trail ran cold, and the Gardens stream came to an end. It is time, then, to move onto the other two streams — or one of them anyway, as I intend to drag this series out to a fifth installment (check back for it in six months or so). The stream we will look at today flows right through another of Toowong’s famous landmarks: the cemetery.

Here lies Langsville Creek

The Toowong Cemetery received its first burial in 1871, but did not open officially until 1875. It sits on ground that is so hard and rocky that in 1870 the appointees of the government’s own Cemetery Trust declared it unfit to receive the dead. But they failed to secure a better site, so were left with no alternative but to establish the cemetery on the slopes of the poor barren broken land of northern Toowong.

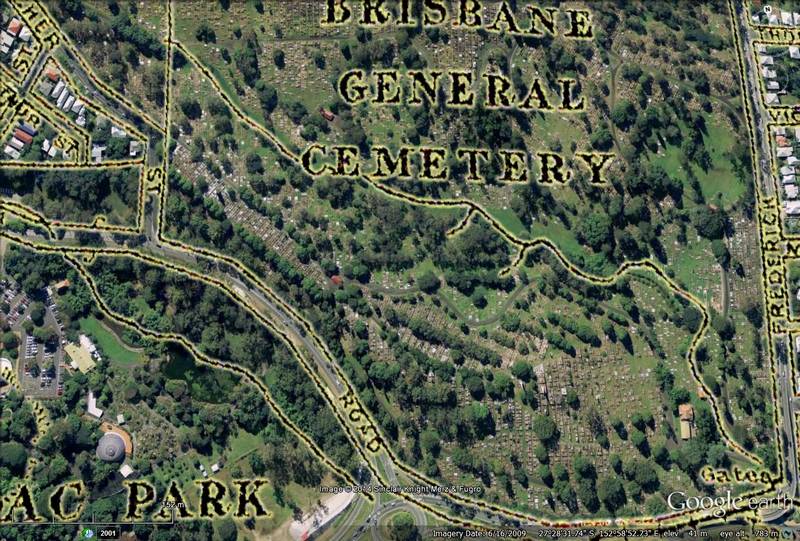

The cemetery stream of Langsville Creek, as depicted in 1929. If you look closely you will see the concrete drain that has replaced the creek in the lower-right part of the image (hovering your cursor over the image will make the current landscape clearer). Across the middle of the image, you can see the clump of trees where some of the creek still exists, and the open fairway that has replaced the remainder.

The map from 1929 reveals that through this broken land flowed a stream beginning near the top of Richer Street and running all the way to the cemetery gates at the bottom of Frederick Street. When you enter these gates today the creek is still there to greet you, but now it is in the form of an open concrete drain.

The visitor

A whole year has passed since I visited the cemetery and took the photos that you see in this post, but there is one part of the visit that I still remember vividly. As I approached the open drain that leads to the culvert under Mount Coot-tha Road (at the bottom-right of the image above), I saw something in the drain move. It was not a lizard or a bird — neither of which I would have been surprised to see — but a small wallaby. Little about the scene made sense, but rather than pinching myself to check that it was real, my first instinct was to kick myself for having left my zoom lens at home. (I thought I would be shooting only drains and gravestones, and did not count on a moving target.) Making do with the lens that I had, I edged closer to get a clear shot, expecting the wallaby to turn and bolt as soon as it sensed my presence. But it hardly moved — either it didn’t notice me, or it did but didn’t care. It just stood there as if in a daze, its back propped up against the wall of the drain.

As I got closer I noticed the animal’s mangy fur and thin body. It did not look well. Finally it saw me and got spooked. It hopped towards the opening of the drain under Mount Coot-that Road, and to my surprise, disappeared inside.

The edge of the cemetery, where the open drain meets the barrel drain that runs under Mount Coot-tha Road.

I waited several minutes with my camera trained on the opening of the drain, but the wallaby did not reappear. Slowly I climbed down and peered inside. There, just a few metres away in the cylindrical brick cavern, was the wallaby, its body slouched and still, its eyes looking vacantly back at me.

The sight was as tragic as it was improbable. How had this wild animal, apparently on death’s door, wound up in a drain in a suburban cemetery? It seemed like a depressing and alien environment for a creature of the bush, but at the same time it was a fitting place to die, if that is what the wallaby had come here to do. There was a sad beauty about the scene as well, in the way the wallaby stood poised at the threshold of light and darkness, its ghostly figure reflected in the inky water, the hues of its mottled fur echoing those of the bricks. Even the bricks alone were beautiful, with their endless receding circles providing the perfect frame. Not that I took all of this in at the time: I was mostly just grateful for such a novel scene and such a cooperative photographic subject.

Eventually the wallaby ambled a few steps further into the darkness, and I decided to let it be. I didn’t hang around to see it come out. I’m not sure that it ever did.

Heading back upstream from where I saw the wallaby, the open drain soon becomes covered. It leads under the lawn of the war memorial and then under a small wooden building that is signed ‘Museum’ but doesn’t look like it has been open for a while. The drain then resurfaces and for a hundred metres or so approximates the path of the old stream, passing through an open lawn, a tangle of small trees and then another lawn where it is surrounded by war graves and adorned by two neat rows of hibiscus. You could almost call it picturesque.

Where gravestones go to die

After passing the hibiscus, the drain meets a footbridge and a thick grove of trees. You could be forgiven for thinking that there is nothing more to see of the cemetery stream of Langsville Creek. But if you stand on the footbridge and look into the trees (or just plunge into them like I did), you will find that the creek is still there.

Well, it’s something like a creek anyway. There was water — orange water — in it when I visited, but I suspect it is dry more often than not. The trees are a motley collection, including some tall gums and pines that are doubtless originals, but also plenty of Chinese elms, umbrellas and other species that don’t look like they belong. The banks are steep and on one side very high, which might help to explain why this section was never turned into drain.

It is also full of rubbish. Not recent rubbish like coke cans and food wrappers, but older, bulkier things like bottles and bricks and chunks of concrete that have quite literally become part of the landscape. Among it all were bits of concrete that looked like pieces of old memorials and headstones. So this is where gravestones go to die.

This short segment of creek in the Toowong Cemetery is filled with bricks, bottles, and what looks like broken bits of old gravestones.

Beyond the grove of trees, there is neither a creek nor a drain: just an open fairway following the original watercourse all the way to the edge of the cemetery. You can see it clearly in the Google Earth image above.

The drowning of Elizabeth Dale

As interesting as it would be to learn when the cemetery stream was drained and what it was like beforehand, I haven’t had time to research it, and there’s a fair chance that I never will. But when I was trawling Trove for articles about Western Creek many months ago, I did come across one interesting story about the cemetery. If you’ve been hanging out for the murder mystery, here it is.

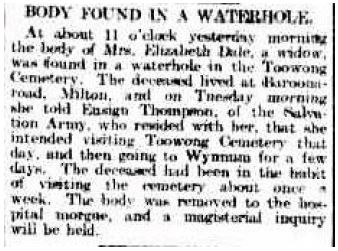

The report in the Brisbane Courier about the discovery of Elizabeth Dale’s body.

On the morning of 1 February 1905, two visitors to the cemetery noticed a body in a waterhole and alerted the cemetery attendant. The body was that of Mrs Elizabeth Dale, a widow who lived at Baroona Road in Rosalie. She had set out on the morning of 31 January to visit the grave of her husband, who had been dead for one day short of eleven years.

At a magisterial inquiry into Elizabeth’s death, the medical examiner reported finding a small bruise beside her mouth and traces of morphine in her stomach. However, observing that her lungs and windpipe were congested, and finding no other evidence of foul play, the examiner concluded that Elizabeth drowned. The morphine in her stomach was at first a mystery, but eventually was traced to a cough medicine that she had been taking before she died.

So much for the murder mystery (sorry!). But how then did she drown? The inquiry offered a few clues. Though only 40 years of age, Elizabeth was in poor health and was frequently prone to fainting. She was also very short-sighted. The inquiry heard that the pool in which she drowned was about 20 feet from a pathway, and close to her husband’s and brother’s graves. Witnesses who went to her husband’s grave after her body was found reported ‘that the long grass on it had been flattened down as if somebody had lain on it’.

Could Elizabeth, stricken with grief, have wandered too close to the waterhole and fainted and fallen in? It’s hard to see how else she could have drowned unless the waterhole was very large and deep — much larger than we would expect to find within the barren lands of the Toowong Cemetery. Heavy rain might change things, but if that was a factor then the inquiry would surely have mentioned it.

Or perhaps it wasn’t a natural waterhole but an artificial dam (for what purpose I don’t know). In any case, I was curious to know where it was, and I wondered if the clues from the inquiry might be enough to lead me there. Yesterday afternoon I spent nearly an hour wandering the low-lying parts of the cemetery looking for the grave of her brother (a Mr Dodd) or her Husband (obviously Mr Dale, though I do not know his first name). If you’ve seen The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, it was much like the scene where Tuco searches for the grave of Arch Stanton, except without the magnificent soundtrack.

Unlike Tuco though, I did not find the grave I was looking for. I had barely started looking when I realised that my chances were virtually nil. Few of the gravestones from the turn of the century remain intact or readable unless they have important names on them. Elizabeth’s husband and brother, and indeed Elizabeth herself, could be in any of the many graves whose headstones are ruined or missing altogether. They might even be in the area just near the remaining part of the creek, where, according to a plaque with an awkwardly constructed poem (at least I think it is a poem), there lay many pauper’s graves. (I have no idea if Elizabeth and her family were poor, but I can’t discount it either.)

I probably never will find the graves of Elizabeth’s loved ones or the place where she drowned, but you can bet that whenever I visit the cemetery in the future I will be scanning every headstone for a Dale or a Dodd, and trying to picture a waterhole somewhere along the old creek’s path. And I will never look at the concrete drain again without wondering if the wallaby made it out. Of course, thoughts of death are never far away in a cemetery. But a cemetery is supposed to be where souls are laid to rest rather than where they are snuffed out. Hopefully the souls of Elizabeth and the wallaby are now resting peacefully just the same.

We shouldn’t forget that the soul of Langsville Creek itself — or part of it — lies buried in the cemetery as well, even if its grave is not marked. With stories like Elizabeth’s drowning in mind, you can see why creeks and waterholes in public spaces get filled in and covered over (not that I would call the open drain safe: you could seriously hurt yourself by falling into it). For me it was a nice surprise to find even a fragment of the old creek still in place, orange water notwithstanding.

Across the freeway, there is a much bigger fragment of Langsville Creek still to be explored. But that will have to wait until the next (and hopefully final) episode. Stay tuned.

Interesting stuff and an interesting hobby. Well done.

Doing this should keep you off the streets 😉

Peter

Angus,

I really enjoyed your article. You always seem to find that extra interesting tidbit to add to the story. As you acknowledge there are many questions that you may never resolve. I do have a question for you. Do any of the early survey maps give an indication of a location of a depression or lagoon area? There is a depression that was filled in with rubble from the Lang Park cemetery which volunteers are trying to piece together headstones from.

The map in this article is the only one I have encountered that shows anything in the cemetery at all other than a blank space. There must have been a survey done of the cemetery at some stage. Perhaps it is lurking in the archives of the lands museum. Or perhaps not. I’ll keep my eyes peeled though.

I didn’t know there was rubble from the Paddington cemetery in the Toowong cemetery. What a fascinating thought!

This is a great story. I lived in Reading Street off Latrobe Terrace and my family used to wonder what happened to the creek that would have flowed down from the water tower hill down to Brigalow Street and through Rosalie.

I have checked the on-line cemetery site and there were two Dales who died in 1894 – Thomas Dale is buried in Portion 1 Section 148 Grave No. 29 and Percy William Dale is in Portion 2A Section 11 Grave No. 12. https://online.brisbane.qld.gov.au/cemeteries/cemeteries_step2.jsp

Ann,

Thanks so much for pointing to the cemetery website – I wondered if there might be a way to look up the ‘residents’ of the cemetery but did not imagine that it could be done that easily. The online tool even shows the exact grave on the aerial photo! I will follow this up: there are a few Dodds listed as well that could be her brother. With any luck, one of them will be close to one of the two Dales that you found.

Thanks again!

Don’t know if this link will work, but her brother Henry Harris Dodd died aged 31 in 1898 and was buried in Portion 11, Section 2, Grave 28…also buried with him is an Elsie G Dodd, 2 years old, died 1896 (apparently his daughter – ?) https://online.brisbane.qld.gov.au/cemeteries/cemeteries_step3.jsp?mapdisplay=137863

Hi Angus and Steven, just a couple of comments. Re the wallaby it is a shame you did not leave info at the office so staff could assist the wallaby although if he followed the creek he would have been able to get out where the rubble was. Speaking of rubble: The broken bits you mentioned are only part of 2500 headstones and grave surrounds that were bulldozed into the creek all the way from near Portion 10 up to the chinese section at the other end just near the end of 7A. Those are mainly not Lang Park/Milton Cemeteries/Paddington monuments, they are Toowong headstones destroyed by Clem Jones in 1974 on. once they were demolished and dumped they were covered over. Yes we do have Paddington headstones in a completely different area which were found accidently around 8 years ago. From 2006 through to 2011 we have been doing archaeological digs with Queensland Uni in the “fairway” you mentioned. 2012 through to 2016 we have been digging them up in a similar exercise and recording all the details most of which have been lost prior to this. They had been moved to the reserve behind Christ Church in 1913 and in 1930 disappeared. The council of the time said it was all rubbish and had been used for roadbase. Instead a lot of them had been secretly dumped in a couple of gullies and covered over and trees planted on top. A large number of those recovered are in perfect condition and even the broken ones easily readable. Some of the ones moved by family from Paddington between 1875 and 1913 with the exhumed bodies re-interred in Toowong rested safely until 1974 when they were also demolished under the orders of the “great” Clem Jones with all the other headstones aforementioned. If you are ever looking for assistance at any time finding a grave or information please email inquiries@fotc.org.au and one of the volunteers will assist you. The museum is open with a large display which is changed regularly of many of the occupants of the cemetery. A staff member in the main office will gladly open the museum for you. When we ourselves are in the cemetery especially on the 1st Sunday of the month it will be open from around 10 til around 12.30. The 1st Sunday is when we do our walking tours of interesting people buried there with stories we have found on them.

Thanks so much for that information, Darcy!