This is the third in a series of posts about Langsville Creek, which was Western Creek’s upstream neighbour on the Toowong/Milton Reach. Before reading this, you may like to look at Part 1 and Part 2 of the series.

I started this series of articles about Langsville Creek as a distraction from my original mission of writing about Western Creek. My new interest soon produced another distraction when I stumbled across a dump of old bottles and cans while exploring Langsville Creek’s headwaters. When I finally finished writing about those bottles and cans a few months later, I took a holiday in Melbourne from which I returned with enough ideas about contrasting topographies to divert myself for several weeks more. Now, having gotten those ideas out of my system, I am resuming work on my first distraction so that some day in the near future I might return to my original goal.

This episode will be pick up the story in the same part of the creek as I got distracted in by those bottles and cans — its headwaters. Having mapped out Langsville Creek’s catchment in the last installment of the series, it is time now to trace where the water flows, and the logical place to start is where the water does: at the top.

Three streams

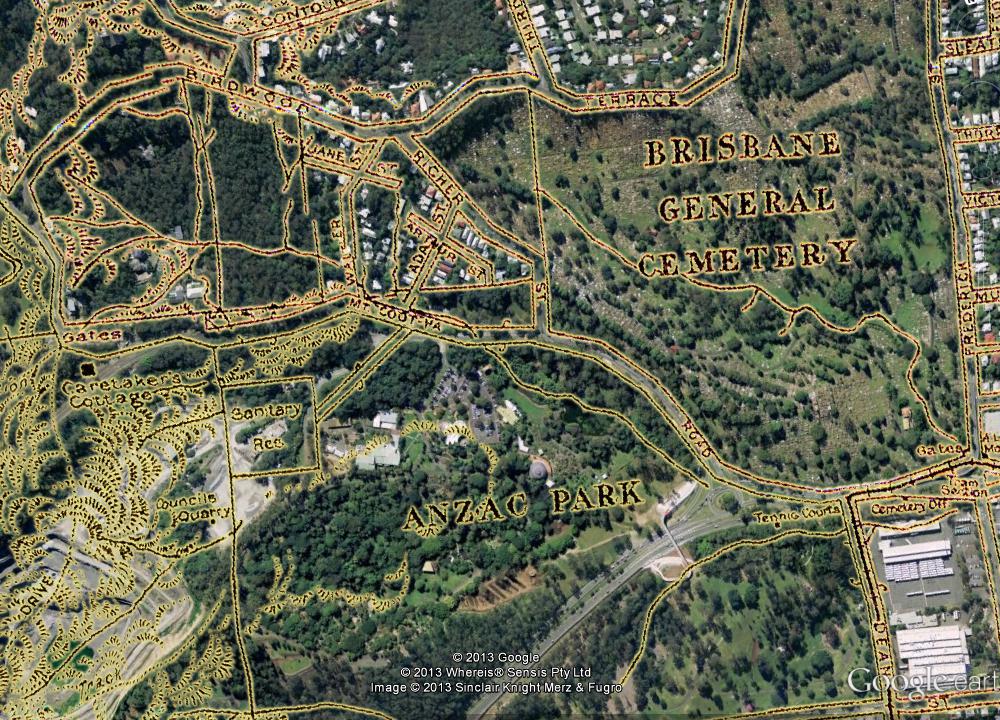

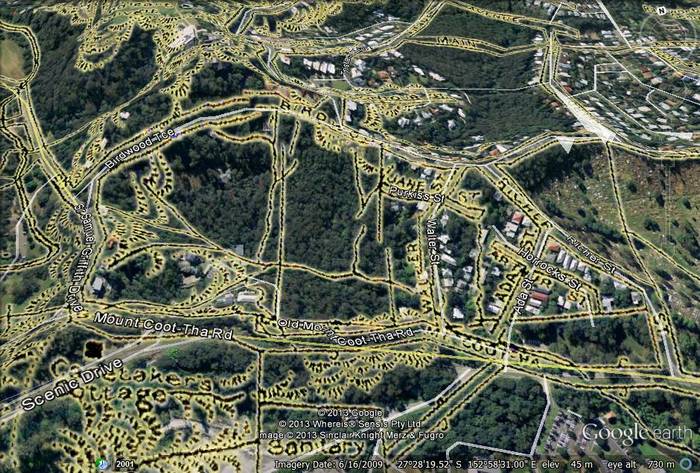

As I noted in Part 1, while several old maps depict the lower parts of Langsville Creek, few maps show its upper reaches. One that does is a map originally published in 1929 and later annotated with the extent of the 1931 flood. The map is held by the Brisbane City Archives and can be accessed online via the Brisbane Images portal on the council’s library catalogue. The portion shown below covers the upper part of the Langsville Creek catchment, of which Birdwood Terrace is the northern boundary. Hovering your mouse cursor over the image (or touching it if you are on a smartphone or tablet1) will reveal how the features on the map align with the modern aerial imagery in Google Earth.

Part of a map of Brisbane dating from 1929 (available online via Brisbane Images). The watercourses shown are the upper reaches of Langsville Creek. (Note that some distortions and artifacts emerged in preparing the map for Google Earth, most notably the giant crack running along Mount Coot-tha Road.)

The map shows three separate watercourses, all of which are part of the Langsville Creek system. There is a stream flowing through the cemetery, another flowing through what we know today as Anzac Park (that is, the area below the Western Freeway; most of what is called Anzac Park on this map is now the Botanic Gardens) and into the bus depot, and a network of gullies below Birdwood Terrace that converge upon a single stream flowing through the Mount Coot-tha Botanic Gardens (marked on the map as Anzac Park). This last stream, and the gullies that feed it, are what I am calling the headwaters of Langsville Creek, and will be the focus of the remainder of this post.

The treetops at Birdwood

The previous part of the tour took in the view of the catchment from the top of Birdwood Terrace before continuing along the ridge of the catchment boundary. This time, we are going straight down the hill, or as near to it as we can without trespassing on someone’s property.

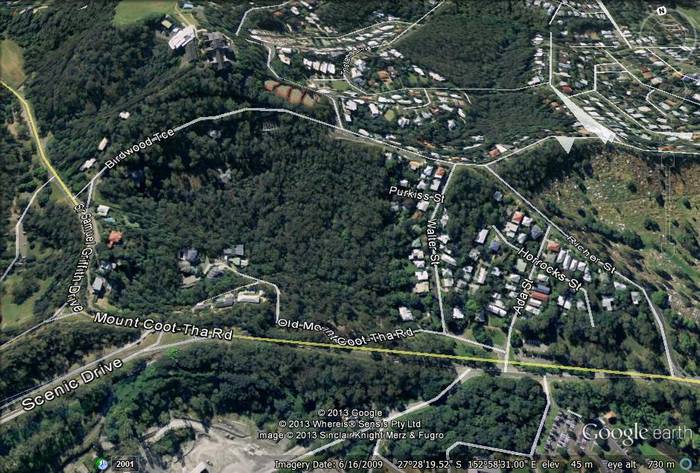

The handful of houses that make up the ‘Treetops on Birdwood’ estate are a very recent addition to the landscape. Historical imagery on Google Earth shows that the blocks were cleared between February and August of 2001, and that some of the houses were still being built in 2009. That this land went undeveloped for so long is hardly surprising when you see how steep it is. In places the ground drops away from Birdwood Terrace almost like a cliff, so the houses on these slopes really are among the treetops. That the treetops are still there is one of the nicest things about this estate. The backyards, such as they are, merge seamlessly into the the surrounding bush, and into the gullies leading to the bottom of the hill.

Despite having lived in this part of Brisbane for most of my life, I had never explored this patch of bush before the present assignment brought me there. Probably this is because the area has no obvious access point from the roads that enclose it — namely, Birdwood Terrace, Walter Street, Mount Coot-tha Road and Sir Samuel Griffith Drive. The area is not large, but it is big enough to lose yourself in while trundling through its network of gullies and dry channels. If there are walking tracks here, I didn’t find them.

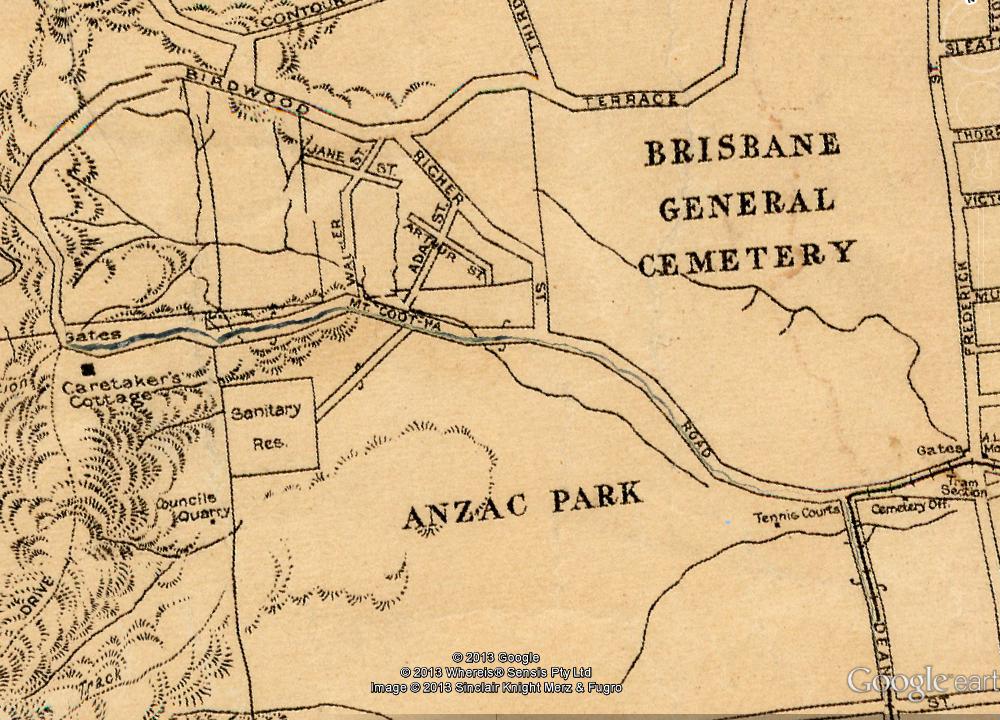

You can see these gullies and channels on the map from 1929. About a dozen separate branches merge first with each other and then with a main channel at the bottom of the hill flowing from west to east. The last branch to join before this channel reaches Walter Street is where I found the collection of old bottles and cans that now have a page all of their own.

The same map as shown earlier, but focussing on the area between Birdwood Terrace and Mount Coot-tha Road. Hovering over (or touching) the image will remove the map features.

As you can see in the photographs below, these channels were all dry when I visited, and I suspect they stay like this nearly all year round. When it does rain, I imagine that the water races down the slopes and through these channels at considerable speed before subsiding almost as quickly.

Somewhere — I neglected to note exactly where, but it must be near where the main channel meets Walter Street — the water must flow into a covered drain which takes it underneath Mount Coot-tha Road. When it emerges on the other side, it meets what you might think of as its sister stream, one that has been fed by an area of roughly the same dimensions and topography as the area we have just explored. All other things being equal, you would expect the hydrology of this other subcatchment to be much the same as the first. But as it happens, other things are not equal, and the hydrology is completely different. For a start, the channels there have water in them.

Langsville’s oasis

Here is what the stream looks like on the other side of Mount Coot-tha Road:

By merely crossing the street, we have gone from dry eucalypt scrub to a subtropical rainforest replete with a tranquil stream. Something doesn’t add up.

The reason is that this rainforest stream, as natural as it looks, is part of an environment that is not entirely natural. The stream runs through the northern edge of the Mount Coot-tha Botanic Gardens, more or less in parallel with Mount Coot-tha Road. A few metres further on, it flows into the large lagoon which, along with the Tropical Display Dome, is among the gardens’ most famous attractions.

Built between 1970 and 1976 to add to the flood-prone City Gardens, the Mount Coot-tha Botanic Gardens cover an area of 52 hectares between Mount Coot-tha Road and the Western Freeway. Most of this area falls within the Langsville Creek catchment. The western part of the site (not shown on the map below, in which west is actually east), which features the native plant communities, sits within the headwaters of Toowong Creek.

Part of the visitor’s map of the Mount Coot-tha Botanical Gardens. The ponds and waterways, while not entirely natural, are all part of the Langsville Creek system. Note that the map does not face north. (Original map)

There are two streams flowing through the Langsville Creek portion of the site. The one flowing near Mount Coot-tha Road is drawn on the lower half of the visitors’ map, flowing towards the lagoon. The slopes in which this stream once began no longer exist. They would now be in tiny pieces scattered across gardens and buildings all throughout Brisbane and who knows where else. In their place today is the empty hole of the quarry, but they can be seen in some detail on the map from 1929. The second stream begins in the gullies of the African and American plant sections. It flows through the exotic rainforest, past a couple of wedding lawns, and is probably linked up with the ponds of the Japanese garden.

At least in parts, both of these streams seem to me to have an improbable amount of water in them, especially when compared with the dry gullies on the other side of the road. This might be due in part to differences in the topography and vegetation, but I suspect that the streams in the gardens have a helping hand. On the visitors’ map you can see that both of the streams begin with a small circular body of water. From what I could tell (and I only investigated one of them), these are storage dams, perhaps the upstream counterparts to the much bigger main lagoon. I’m unqualified to even guess at how the system works, but somehow, the water flowing through these streams and their lagoons must be regulated, if not also supplemented, as part of the site’s operations.

Whether natural or not, the results are rather splendid. In some places the channels look entirely natural, while in others they look more like the ruins of an ancient city that has been swallowed up by the forest.

In all likelihood, not even the less exotic of these streams and lagoons resemble the original headwaters of Langsville Creek. But they are thriving ecosystems nonetheless, and they enrich the catchment both aesthetically and environmentally. It’s a pity, then, that this little river of life comes to an end so suddenly.

Langsville’s Legacy

If you look closely at the map from 1929 at the top of this page, you will notice that a major piece of infrastructure is missing. There was no Western Freeway in 1929, and there wouldn’t be for another 50 years. The Western Freeway was completed in 1979, not long after the Botanic Gardens opened. Between Toowong and Indooroopilly this arterial road cuts a swathe through 2km of bushland that previously connected these suburbs to Mount Coot-tha Forest. Helped by the enormous roundabout at the junction with Mount Coot-tha Road, the freeway also separates the Botanic Gardens from the rest of Toowong. At least nowadays pedestrians can safely cross this divide, even if wildlife can’t. Before the overpass was built, to get to the gardens or the cemetery from Anzac Park or the bus depot you either had to walk all the way to Milton Road or run for your life across the four lanes of speeding traffic.

As if the freeway weren’t enough, in recent years a new infrastructure project has widened this corridor further still. To see it, hover your mouse cursor over the image below.

Hover over the image (or touch it) to see the construction site of the entrance to the Legacy Way tunnel. The initial imagery is from June 2009, while the newer imagery, sourced via Queensland Globe, is from September 2012. (animated GIF version also available.)

If you’re like me, you would have gone back and forth between these two images at least 20 times before you started to get bored. (If you’re using a mobile device and can’t go back and forwards, try this animated GIF version.) Even now I can’t quite compute what I am seeing, such is the scale of the works and the contrast with what was there before. It looks to me as if a strip of the earth’s skin has been peeled away by a surgeon to reveal the flesh underneath. This is the construction site for the entrance to the Legacy Way tunnel, which when completed will allow commuters to go underground at Toowong and magically reappear 4.6km later at Kelvin Grove.

The temporary shed installed to reduce noise and dust from the machines boring the Legacy Way tunnel.

The structure at the bottom of the frame, which may have since been dismantled, is designed to muffle the noise and contain the dust from the boring machines. According to a sign posted at the site, the structure is 89 metres long, 77 metres wide and 29 metres high. It is the biggest garden shed I have ever seen.

As with the shed, the rest of the site has surely changed since I took these pictures in May 2013, but at the time it was mess of barriers and pathways, materials and machinery. In amongst it all was a network of temporary drains and ponds. Flowing somewhere amid this chaos, or perhaps underneath it, is the outflow from the Botanic Gardens and the Birdwoord Terrace gullies. This is where Langsville Creek meets the Legacy Way.

When looking at these images, keep in mind that the finished project will not look quite so ugly, or take up so much space, as the construction site. In fact, according to the Legacy Way website, the site’s rehabilitation will include an expansion of the Botanic Gardens, which among other things will feature an 18-million-litre storage lagoon. Langsville Creek’s artificial oasis will be hemmed in even more tightly by the growing mote of bitumen and concrete, but on the bright side, it will be bigger and more drought-proof than ever.

The physical boundary imposed by the Western Freeway and Mount Coot-tha Road is also where I am going to draw the line on today’s excursion. Across those roads there is much more to explore, and I hope to pick up the story again soon. As always, the only thing standing in the way is another distraction.

Notes:

- Unfortunately, if you are using a smartphone or tablet you probably cannot switch back to the original image by touching it again. To see it, you may need to refresh the page. ↩

Hi Angus, there is another section of the Creek which you have not covered between the Cemetary and the Sylvan rd Chinese gardens, it ran along the back of the houses on the North Side of Sylvan road, and had a small drain branch at the bottom of Quinn Park.

Hello Dr John and Angus,

My memory is the creek in 1955 was open from and flowing at corner of Miskin Street. From there to St Othyths Street is a blank.That creek ran down the laneway between St Othyth Street and Croyden Street. It crossed Croyden Street under a short wooden bridge as an open drain/ creek and ran north up Bayliss Street turning right through the chinese gardens then entering Toowong memorial park approx 40 metres from Sylvan Road. My family moved into the corner shop opposite in 1955, coining it “Macs Cash Store”. We kids used to swim and catch yabbies in the ponds of the creek roughly where the Legasy Way tunnel entrance is now. Back down at the park, the chinese gardeners were not terribly friendly but also, not hostile. The creek bed between the chinese garden and the railway line was cleared and 4 foot dia concrete pipes installed and covered over with coal ash around 1956. It was then that the playground was equiped with a swing, jungle bar, merry go round and a decomissioned Steam roller. Memory is as accurate as a 75 y/o with a little dementia would have. cheers