A story in the Brisbane Times this morning, titled Buyers less fearful of flood zones, made me a little bit mad.

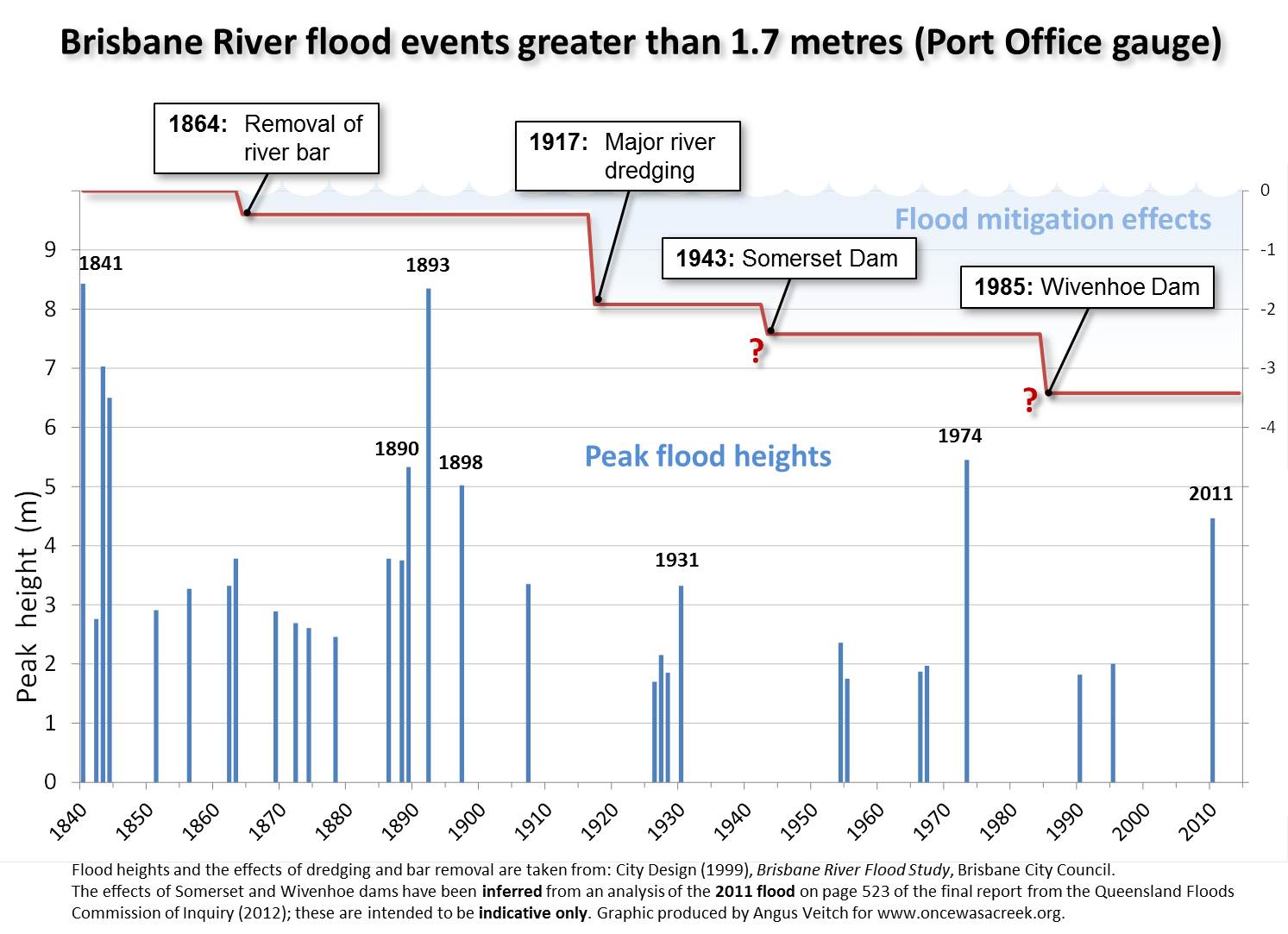

Though I try not to buy into the blame game around the 2011 flood, I suspect that the real estate industry is partly responsible for the false sense of security that set in after Wivenhoe Dam was built. I have no proof of this; it is just a hypothesis. But it stands to reason that someone whose job is to sell houses will downplay the risks of flooding any way they can. Buyer beware.

Whether or not real estate agents have done it in the past, they certainly seem to be doing it now.

According to agents working in river precinct suburbs, the percentage of buyers willing to consider properties previously flooded in 2011 has increased significantly because they feel assured that the Wivanhoe Dam did its job in mitigating another flood over the Australia Day weekend.

Granted, this boost in buyers’ confidence is not necessarily the doing of real estate agents. People make their own assessments of risk based on events, and make their own decisions accordingly. Whether those assessments and decisions are justified or wise is an open question, but it is one that needs to be answered with some understanding of the facts about the 2011 and 2013 flood events, what role the dam played in each, and how the two events are comparable. I won’t pretend to have all of those facts. But I humbly suggest that not many real estate agents do either.

The article continues, quoting Brad Robson of Brisbane Real Estate:

“They’re happy that the dam worked. There was a truckload of rain and nothing flooded so it’s given them the confidence to go ahead and make a purchase”

John Johnston, of Johnston Dixon, said the Brisbane River needed a proposed class action by residents to succeed in order to clear its name.

“These properties should never have experienced the flooding that they did in 2011 and the latest weather event last month supports that,” he said.

“The mitigation capacity of the Wivanhoe have now been proven. I’m confident that if this class action goes through, it will largely clear the Brisbane River’s name and buyers will no longer be afraid to purchase near the river.”

Torwood Street during the January 2011 flood

There you have it: the smallness of the 2013 flood proves that the 2011 flood did not need to happen. It was all the fault of the dam operators. They are guilty, and the river is innocent — we just need to ‘clear its name’!

I’ll stress again that I do not know all of the relevant facts. But in case someone else has the inclination to go do some homework, I suggest that the following questions would be a good place to start:

- Could it be that the 2013 flood was smaller than the 2011 flood because there was less rain?

- Where did the “truckload of rain” that fell in 2013 actually fall? According to our Premier and the Bureau of Meteorology, the flooding in 2013 was caused by rain that fell in catchments that discharge to the Brisbane River downstream of Wivenhoe Dam. Suppose that even more rain (a shipload?) fell in those catchments: would the dam save us then?

- Could there be any truth in the Flood Commission’s finding, stated on page 524 of the Commission’s final report, “that, allowing for the limits of the strategies in the Wivenhoe manual, the flood engineers achieved close to the best possible flood mitigation result for the January 2011 flood event”?

I’m not presuming that the dam manual is perfect, that the dam operators did a perfect job, or that there are not lessons to be learned from the way the 2011 flood was managed. And I’m not offering an opinion on whether a class action against the government’s management of the flood is warranted. But I do think that comments such as those above from the real estate industry are grossly irresponsible, and are the absolute last thing we need if we are to to learn from past events and become better informed about the nature of flood risks in Brisbane.

Buyer beware.