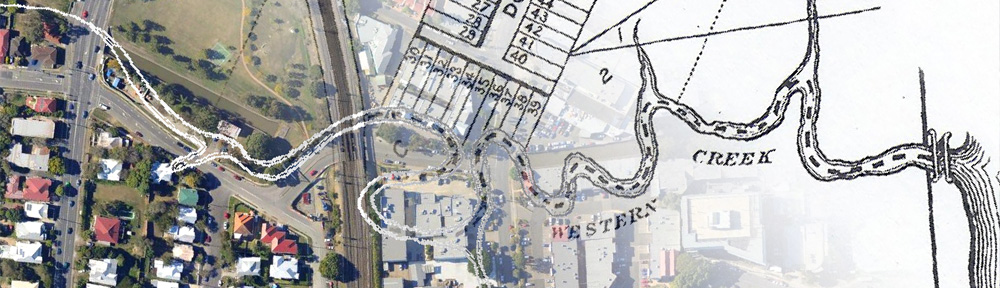

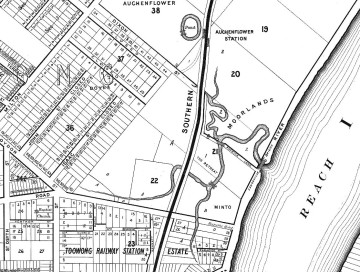

This is the third in a series of posts about Langsville Creek, which was Western Creek’s upstream neighbour on the Toowong/Milton Reach. Before reading this, you may like to look at Part 1 and Part 2 of the series.

I started this series of articles about Langsville Creek as a distraction from my original mission of writing about Western Creek. My new interest soon produced another distraction when I stumbled across a dump of old bottles and cans while exploring Langsville Creek’s headwaters. When I finally finished writing about those bottles and cans a few months later, I took a holiday in Melbourne from which I returned with enough ideas about contrasting topographies to divert myself for several weeks more. Now, having gotten those ideas out of my system, I am resuming work on my first distraction so that some day in the near future I might return to my original goal.

This episode will be pick up the story in the same part of the creek as I got distracted in by those bottles and cans — its headwaters. Having mapped out Langsville Creek’s catchment in the last installment of the series, it is time now to trace where the water flows, and the logical place to start is where the water does: at the top.

Continue reading