Way back in January, I reported that the City Council had begun constructing a floodgate at the mouth of Western Creek. This is the spot where the Milton Drain meets the river, right next to where the dilapidated shell of the old floating restaurant still stands. If you have passed by this spot in the last few months, you will have seen that the construction is complete: Western creek finally has its floodgate.

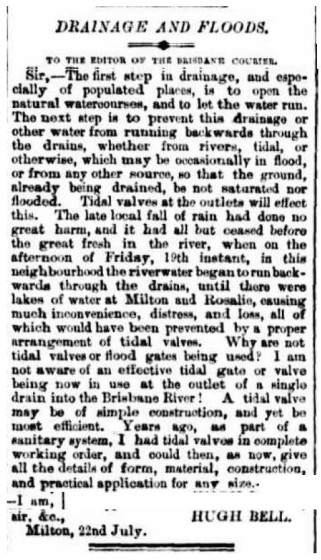

Hugh Bell’s letter to the editor of the Brisbane Courier in July 1889, arguing for the use of tidal valves to prevent flooding in Milton and Rosalie.

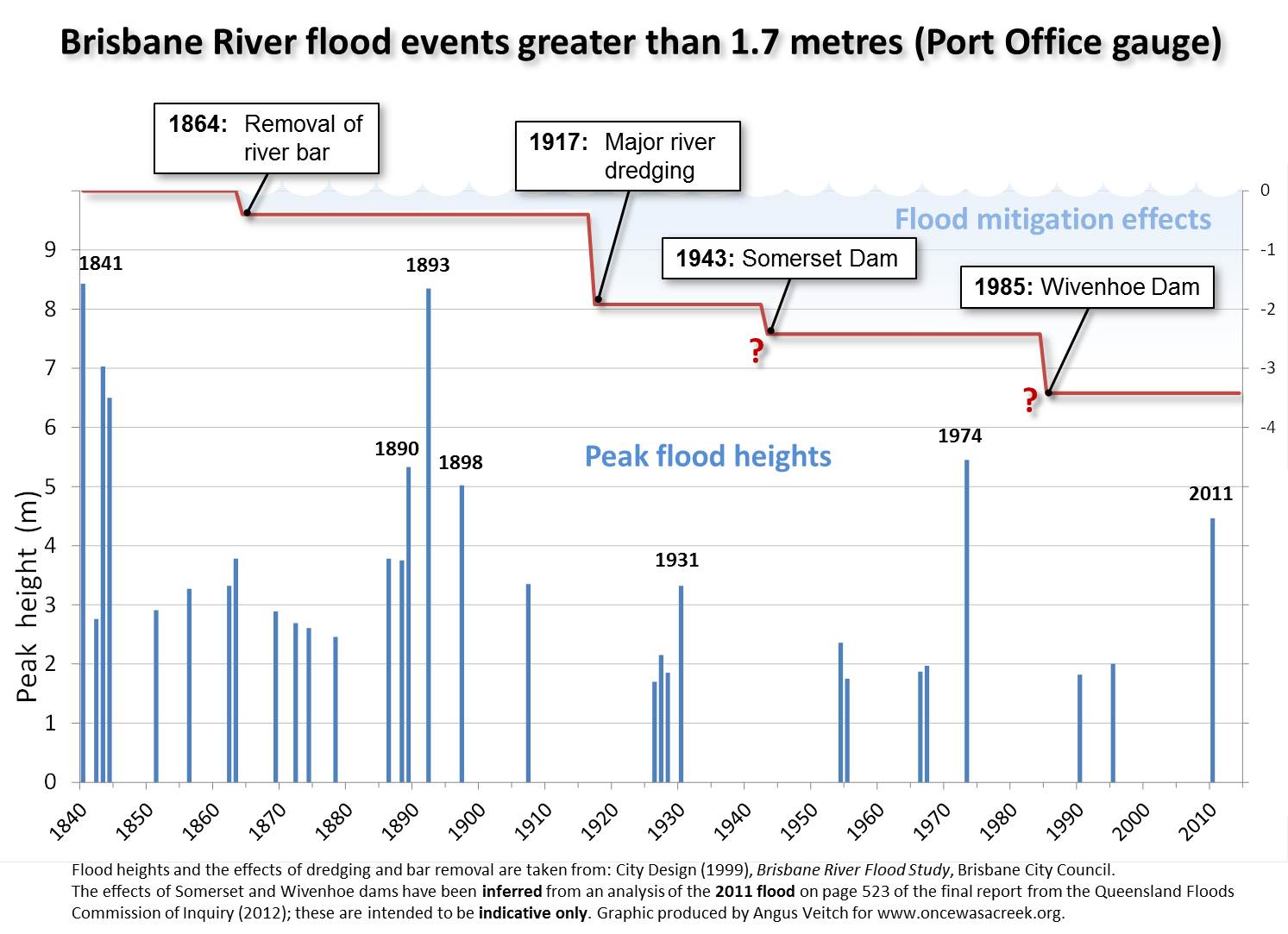

I say ‘finally’ not because more than three and a half years have passed since the 2011 flood (some people might even call that response time quick), but because more than 125 years have passed since a floodgate at the mouth of Western Creek was first proposed. In July 1889, while the mud was still drying from a flood that peaked at 3.75m on the Port Office gauge (about 2 ft lower than the 2011 flood), a Milton resident named Hugh Bell wrote to the Brisbane Courier, asking “Why are not tidal valves or flood gates being used” to prevent flooding in Milton, Rosalie and other low-lying suburbs? This question was no doubt raised again in March of the following year, when the river peaked at 5.33m — just under the mark of the 1974 flood. In response, the Toowong Shire Council in October 1890 unveiled an ambitious whole-of-shire1 drainage scheme which featured floodgates at the end of Western Creek and Langsville Creek. But the council could not afford to build the whole scheme, and so built it piecemeal instead. Some components, such as the drain through Red Jacket Swamp, took years to get finished, while the floodgates never materialised at all.

But the idea didn’t die: it resurfaced after every flood, only to recede again with the memory of the floodwaters. It probably sunk into near-oblivion after the completion in 1985 of Wivenhoe Dam, which — if you believed the real estate industry — was supposed to save Brisbane from ever flooding again. But when the flood in January 2011 proved — unless you believe the real estate industry — that Wivenhoe Dam is not a bottomless pit after all, attention turned once again to more localised methods of flood mitigation. The Brisbane City Council commissioned a study into backflow prevention, and since 2012 has been rolling out the installation of floodgates — more properly known as backflow prevention devices — at prioritised spots along the river. Continue reading

Notes:

- The Toowong Shire fronted the river all the way along the Milton Reach, from Boundary Creek (where Boomerang Street is today) to Toowong Creek (near Gailey Road). The boundary between Toowong and Ithaca shires began where the railway line crossed Boundary Creek, and continued along the railway until it reached Baroona Road, then known as the Boundary-road because it divided the two shires all the way up to the top of what is still called Boundary Road today. (Back then, Baroona and Boundary roads were joined at the upper end of Norman Buchan Park.) ↩