Note – many of the pictures in this post contain two images, which flip back forth when you hover your mouse over them. On a mobile device these images will switch when you touch them, and then switch back when you scroll away … if you are lucky. For best results, please view this article on a desktop or laptop.

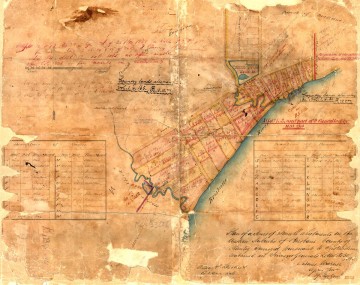

Figure 1. A survey plan of the Milton area in about 1850 (B.1234.14), held by Queensland’s Museum of Lands, Mapping and Surveying.

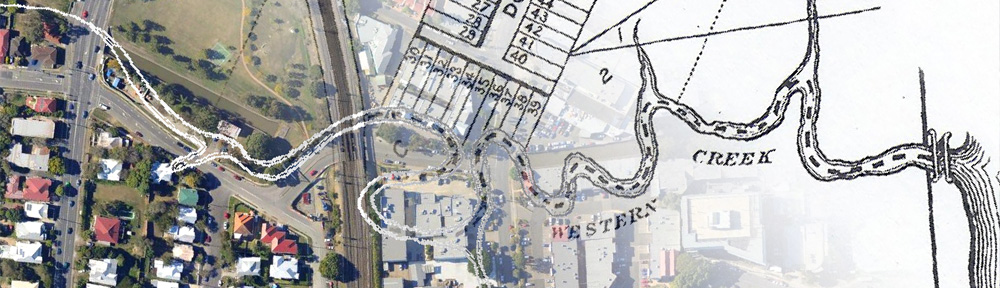

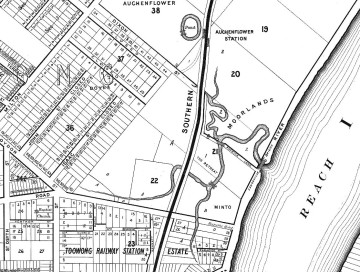

In an earlier post called The Waters of Milton, I explored a survey plan of Milton drawn in 1850 (Figure 1). Survey plans are valuable historical artifacts because they generally represent the first efforts to capture the landscape on paper. They reveal natural features that have long since vanished, such as creeks, swamps and even hills. They also provide insights into how the colonists saw the land, indicating its potential uses and specifying how it was to be divided up among its new owners.

Since writing that post, I have obtained several more digitised survey plans of the Milton Reach and Western Creek areas, thanks to the assistance of the Museum of Lands, Mapping and Surveying, which is part of the Queensland Department of Natural Resources and Mines. I look forward to featuring them all in articles in the future, but today I will explore just one of them. This particular plan carries the catalogue name of M.31.65. I have no idea what that means, but then there is a lot about these plans that I am still fuzzy about. Some of the surveying markings may as well be hieroglyphs to me, but thankfully there is much that can be gleaned even without specialist knowledge.

Unlike the Milton plan, this one depicts an area inland from the river. I’ll get to the precise area shortly, but first we need to dispense with some formalities.

Continue reading