Backflow to the Future…

or: How we learned to stop worrying and love the floods

Duckbill season

If you’ve walked along the riverside bikeway at Milton recently and paid close attention to the riverbank, you may have noticed one of these:

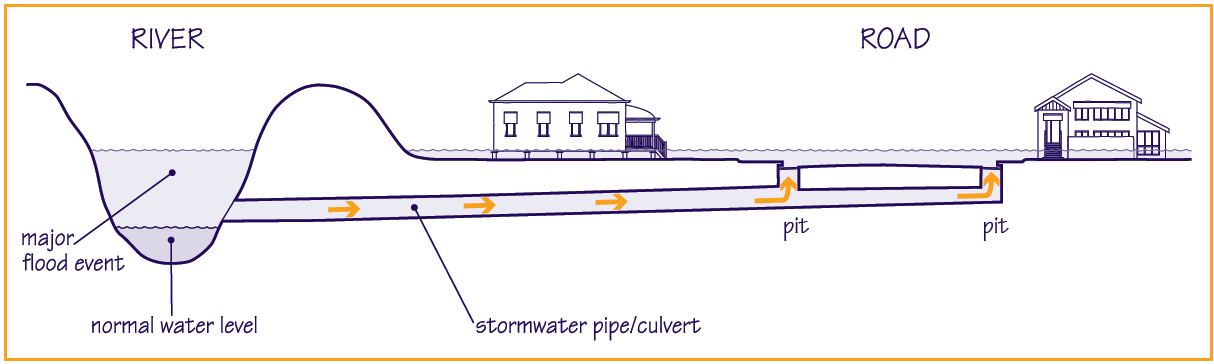

This is not a piece of misguided public art (and hey, we’ve all seen worse). It is called a duckbill valve, and its purpose is to let water flow from the drain into the river but not the other way around. If you don’t think that’s enough to justify its ridiculous appearance, then take a look at the diagram below. Lifted from the Brisbane City Council’s fact sheet on backflow flooding, this diagram illustrates how many parts of Brisbane, including Milton and Rosalie, were flooded in January 2011. The water in these areas did not spill over the riverbanks, but instead snuck in through the stormwater drains that connect to the river.

Concept diagram of backflow flooding, taken from the Brisbane City Council’s factsheet.

This duckbill valve is just one of several backflow prevention devices that the Brisbane City Council installed along the river last year. Just nearby at Milton you can find another duckbill as well as a flap-gate, which does essentially the same thing but looks much more sensible.1 Backflow prevention devices have also been, or are being, installed in the Moray Street drainage system in New Farm, and in the Margaret Street, Alice Street and Charlotte Street stormwater systems in the CBD. And if the council’s website is to be believed, these are just the beginning.

The floodgate gap

In response to the 2011 flood, the Brisbane City Council commissioned an investigation into the feasibility of using backflow prevention devices to mitigate flood impacts in flood-prone parts of Brisbane.

The 2011 floodline over the drainage systems of Cribb Street (foreground) and Castlemaine Street (Boundary Creek, near the stadium).

The investigation has focussed on three case study areas — the CBD, Rosalie/Milton and New Farm — while also reviewing other areas along the Brisbane River that may benefit from backflow prevention devices.

In addition to the areas where devices have already been installed, the council has identified 11 other priority drainage systems that will receive funding over the next few years. These systems include Castlemaine Street in Milton (the old Boundary Creek), Milton Drain (Western Creek), and just upstream of the Wesley Hospital (what used to be Langsville Creek).

The Cribb Street drainage area in Milton, where the duckbills have already been installed, is shown in the foreground of the image to the right. (Before this area was developed, there was a large lagoon in roughly the same location.) Also shown on the same image is the floodline in the Castlemaine Street (Boundary Creek) system, which runs past Suncorp Stadium.

How to tame the Milton Drain

An example of a penstock valve

An example of a flap gate.

Installing flood-prevention devices in the Castlemaine and Cribb street systems is relatively straightforward because these drains meet the river as pipes onto which duckbills or flap-gates can be readily fitted. The Langsville Creek system ends in a series of square and round concrete culverts which could be closed off using penstock gates, which are manually raised or lowered into position when needed.2

The entrance to Milton Drain presents a bigger challenge. According to the recommendations of the Council’s investigation, there are two structures here onto which backflow devices could be mounted. The first is the bridge along the bikeway, across which a series of flap valves could be installed. But this would only protect against a relatively small flood (one that could be expected to occur on average every 20 years). To protect against a flood as big as the one in 2011 (estimated to be a one-in-120-year flood3), the backflow would need to be blocked by a barrage of penstock valves reaching all the way up to the bottom of Dunmore Bridge (Coronation Drive).

If you take a walk under this part of Coronation Drive, you can see what an inconvenient space this would be to build in. Not only is the channel large and irregularly shaped, but there is also a pedestrian walkway under the road which would essentially need to be sliced in half to allow the penstock gates to rise.

In other words, some serious engineering would be needed to stop floodwaters getting into Milton Drain and the Western Creek catchment. But then again, it’s hardly the Panama Canal. And a glance at the picture on the left shows how big an area would saved.4 Approximately 47 hectares (0.47km2), including 5.9km of road and 1,078 properties in this area were affected in January 2011, all by water coming in through Milton Drain.5

If the river rose above the level of Dunmore Bridge (like it did in 1974), a backflow prevention device would not prevent the area from being inundated. But it would hold off the inundation until the riverbank is broken, thus buying valuable time in which both people and property could be moved moved to higher ground.

A case of history repeating

Despite posing some challenges, the likely benefits of preventing backflow into the Western Creek catchment seem pretty clear. So clear, that you might wonder why it wasn’t done years ago. After all, it’s not as if floods in the Brisbane River are anything new; on the contrary, they happened more often in the past than they do now. Floodgates are nothing new either: they have been used in various parts of the world for centuries. The dots are there just waiting to be joined.

Not surprisingly, the dots have in fact been joined before, and not just once. Proposals for mitigating floods in the Milton area have been floating around for years. After just about every major flood they get rehashed or reinvented, they get talked about in the newspapers, and they get forgotten again. The details vary, but the premise is the same: with some straightforward engineering, Milton can be protected from all but the biggest floods.

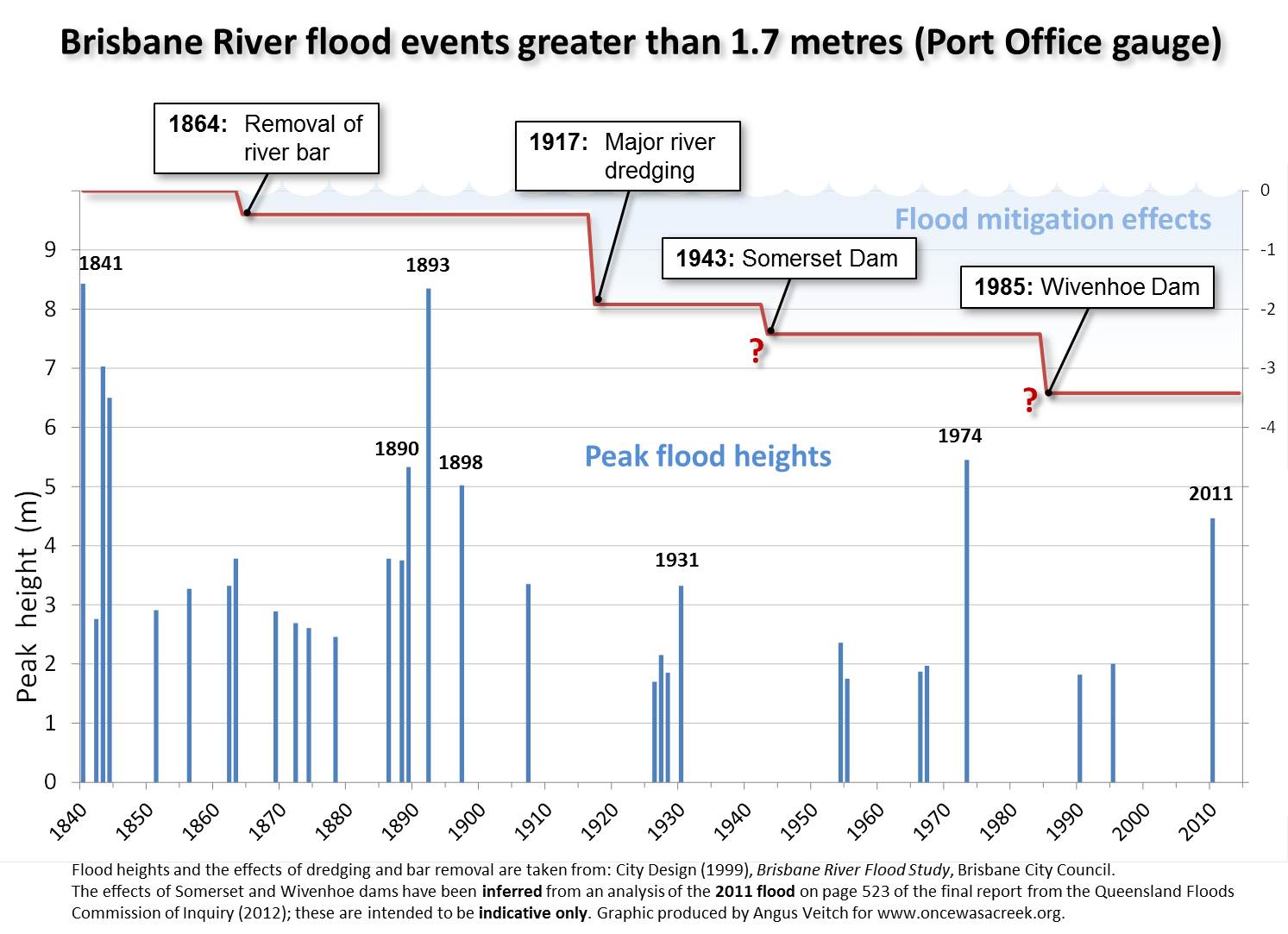

Flood events greater than 1.7m in the Brisbane River since 1841. Also shown are the estimated mitigating impacts of river works and the two dams. All data are sourced from the Brisbane River Flood Study except the effect of the two dams, which is indicative only and has been inferred from an analysis on page 523 of the final report of the Flood Commission of Inquiry.

Reverend Roberts’ sermon on flood mitigation

‘It is to me a marvel that such a scheme as is here suggested for the districts referred to was not attempted years ago.’

–John W. Roberts, Milton

The Brisbane Courier, 1898.6

The 1890s was a big decade for floods in Brisbane. The warm-up act was provided by the floods of 1887 and 1889, which peaked at 3.78m and 3.75m respectively. The main show began in March 1890, when the river peaked at 5.33m. But even this was just a teaser for the Great Flood (or rather, Floods) of 1893. On the 5th of February 1893, the river peaked at a whopping 8.35m. Two weeks later the river peaked again at 8.09m. In the intervening time there was a minor flood of 2.15m.7 As if to rub salt in the wound, another flood hit in June, this one reaching about 4.2m8 despite occurring in what is traditionally the dry season. To close off the decade, the Brisbane River managed one more major flood, peaking at 5.02m in January 1898. To put these events into perspective, the 2011 flood peaked at a ‘mere’ 4.46m.

One might expect such a succession of disastrous floods to give cause for reflection on whether Brisbane had to keep living this way — or indeed if it could afford to. On the 9th of February, 1898, the Milton resident John W. Roberts was reflecting on exactly this when he picked up his pen and wrote a letter to the editor of The Brisbane Courier.

The Reverend John W. Roberts was a pastor at the Milton Congregational Church, which stood until 19709 on the corner of Baroona and Haig roads. Between 1895 and 1900 (at which point he moved to Hobart10) Roberts had numerous letters published in The Brisbane Courier on topics including gambling laws, religious instruction in state schools, orphanages, and the draining of Red Jacket Swamp.11 In the wake of the 1898 flood, he turned his pen on the Railway Comission’s plan to spend £7,00012 raising the railway line in the flood-prone areas around Western Creek and Langsville Creek:

Makeshift bridge of railway wagons during the 1890 flood in Auchenflower. (State Library of Queensland)

It is presumed that the Railway Commissioner and others will be interested to know how it is possible for a much smaller sum, say, £1000, not only to keep the railway line at the creek referred to clear of flood water, but also the whole of the Rosalie and Torwood districts. By raising the River-road by 3ft for about 200 yards adjacent to the outlet of the creek into the river, and by placing a lock or floodgate at Cribb’s Bridge, the flood water would be effectually prevented from inundating the railway at the point referred to and the localities mentioned.13

Roberts was proposing to mitigate against future floods as high as the one that occurred in 1890, which peaked at 5.33m near the CBD, or 87cm higher than the 2011 flood.14 Even today, this would require building a levee or raising the level of Coronation Drive (the River-road) not only at Dunmore Bridge, which was barely high enough to contain the 2011 flood, but also at the intersection with Land Street, which was inundated in 2011. Thankfully though, a flood as high as in 1890 is considerably less likely to occur today. Since 1890, many of the lower reaches of the river have been deepened, widened and/or straightened so they can accommodate greater flows. In addition, Wivenhoe and Somerset dams provide a storage buffer that, if used strategically, can reduce the peak flows of a major flood. If the 1890 event occurred today, it most likely would have peaked low enough to be contained by floodgates alone.15

Preaching to the choir

Reverend Roberts was not a lone voice in arguing for a flood mitigation scheme in Milton and Auchenflower. In his letter he insisted that the idea was by no means original to himself, but was rather “a subject of general conversation and agreement in the district”. Sure enough, the next day’s issue of The Brisbane Courier featured a letter of support from W.H. Spode, a resident of Bayswater.16 Two days later there appeared another endorsement of Roberts’ proposal, this time from W.A. Cribb (grandson of Robert Cribb), who lived at Park Road. The central point of both letters was the same: that whatever the cost of the proposed flood mitigation works, the costs of a major flood were much greater. Reflecting on the flood that had just passed, Cribb wrote:

Milton Congregational Church (left) and Milton Primary School (middle distance) under flood, 1890. (State Library of Queensland)

Any thoughtful person, but more especially a victim of the flood, viewing the different large expanses of water in the Milton district in the light and stillness of the early dawn when the flood of last month was at its height and just beginning to recede, would have been depressed at the sight of the hundreds of homes more or less submerged in the silent and relentless flood. But upon investigation the feeling of depression would quickly give place to that of mingled indignation and regret when it was discovered that so great a loss might have been prevented by so small an expenditure.17

This gulf between costs and benefits is unlikely to have closed since 1898. If anything, it has probably widened. For while the likelihood of a major flood has been dampened, the scale of the consequences has been amplified by continued development on the floodplain. While the 2011 flood was smaller than those of the 1890s, the cost of damage done to homes, businesses, roads and other infrastructure must have been much greater.

‘If it cost five times as much as was mentioned in the letter it would be cheap, considering the saving to residents and property-owners that would be effected.’

–W.H. Spode, Bayaswater

The Brisbane Courier, 1898.18

A man, a plan, a floodgate — Milton!19

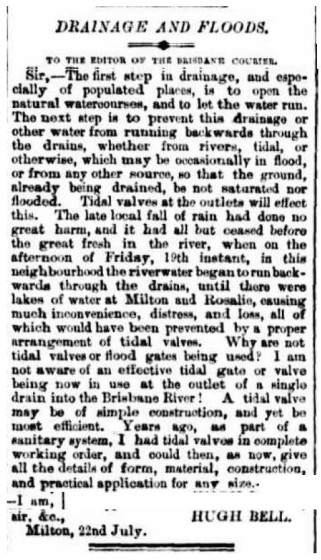

Letter to the editor from Milton resident Hugh Bell, arguing for the use of tidal valves to prevent flooding in Milton and Rosalie. (The Brisbane Courier, 24 July 1889, p3.)

The idea of flood-proofing Western Creek can be traced back even further than 1898. Almost nine years earlier, Hugh Bell, another Miltonite, wrote a letter to The Brisbane Courier making the very same points as J.W. Roberts. Writing just days after the flood of July 1889, Bell expressed his incredulity that tidal valves or floodgates were not already being used to prevent flooding in Milton and Rosalie. He emphasised how readily they could be designed and installed, even offering to provide “all the details of form, material, construction, and practical application for any size”.20

Bell’s enthusiasm for floodgates appears to have been shared by W.E. Irving, the engineer for Toowong Shire. In October 1890, Irving unveiled his plans for a drainage scheme for the whole of the shire. Included in the scheme were floodgates at the ends of both Langsville Creek and Western Creek. The scheme for the Western Creek system ran as follows:

The Red Jacket Swamp and Torwood drain will start at Baroona-road at the 6ft brick culvert which has just been completed by the Ithaca Shire Council. It will form a continuation of the Ithaca drain, but instead of being covered will be an open invert drain. It will run aoross the Red Jacket Swamp, passing close to the State school fence, to the south corner at the junction of Bayswater-street and Heussler-terrace. Thence it will run along the south boundaries of portions 43 and 44 to the old wooden culvert on the Milton-road, where it runs into Western Creek, which flows into the River at Dunmore bridge, near Mr Robert Cribb s residence, on the river road, where it is intended to construct a large brick culvert with a floodgate, and then fill up the old creek the full width of the road, thus doing away with the present unsightly and inconveniently narrow wooden bridge.21

Irving’s proposal would have turned the mouth of the creek into a closed brick culvert instead of the semi-open channel that remains today. Building a floodgate into such a culvert would have been relatively easy. But the Toowong Shire Coucil of the day lacked either the funds or the vision to see the scheme through. Some components, such as the drain through Red Jacket Swamp, sat on the back-burner for years, while others, such as the floodgate, never materialised at all.

But the idea never died. All that was needed to bring it back into fashion was another flood. In 1909, presumably in response to the flood of 1908, Alderman Morris of the Ithaca Town Council presented a petition “requesting the erection of a flood gate at the entrance to the Milton drain”.22 The petition was duly referred to the works committee, who in turn must have referred it to the filing cabinet.

‘…the riverwater began to run backwards through the drains, until there were lakes of water in Milton and Rosalie … all of which would have been prevented by a proper arrangement of tidal valves.’

–Hugh Bell, Milton

The Brisbane Courier, 1889.23

The Dam or The Bomb

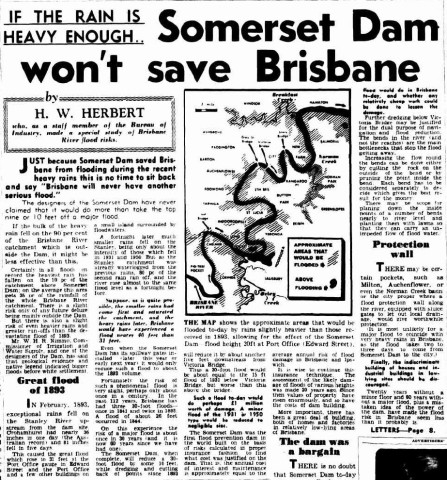

H.W. Herbert’s article published in The Courier Mail, 4 March 1953.

In March 1953, The Courier Mail published a feature article written by H.W. Herbert24 entitled “If the rain is heavy enough… Somerset Dam won’t save Brisbane”.25 Herbert credited Somerset Dam with saving Brisbane from being flooded earlier that year, but warned that the dam would do little to stop a flood as large as the one of 1893. Herbert thought that a second dam on the scale of Somerset would be hard to justify when the other priorities of the day (among which he listed worrying about atom bombs) were weighed up against a such an “infrequent risk” as a major flood. However, he urged the investigation of cheaper, smaller-scale works that could lessen the damage of a flood. Among other locations, he singled out Milton and Auchenflower as places where “a flood protection wall along the river, equipped with sluice gates to let out local drainage, would give worthwhile protection.”

‘When atom bombs are a risk we are not likely to worry much

about the type of flood which only comes once a century.’

–H.W. Herbert

The Courier Mail, 1953.26

Twenty-one years passed before the flood Herbert warned about finally came. Somerset Dam was powerless to stop the flood of 1974, and suburbs like Milton and Auchenflower were as exposed as ever to the waters that encroached through the drains and over the riverbank. This time though, there was a definitive response. Although Herbert had reservations about it 21 years earlier, a second dam was now seen as the way to go. Completed in 1985,27 Wivenhoe Dam provided 1.45 million megalitres flood mitigation storage over and above its usual operating capacity of 1.15 million megalitres.

Now, with not one but two dams watching over it, Brisbane could finally relax . . . right?

‘There may be certain pockets, such as Milton … where a flood protection wall along the river, equipped with sluice gates to let out local drainage, would give worthwhile protection.’

–H.W. Herbert

The Courier Mail, 1953.28

The lonely floodgate

It may be unfair to characterise the history of flood mitigation in Milton as all talk and no action. A report in The Brisbane Courier on the flood of March 1890 suggests that a floodgate had actually been installed in the Cribb St drainage system as early as 1889:

The residents of the Milton Estate, that is between Cribb-street, Park-road, the railway, and the river suffered more severely than any others in the shire. Here something like thirty-five houses were flooded to a depth varying from 1ft to almost complete immersion, and it would be very difficult to estimate the amount of damage done. The residents appear to have thought themselves tolerably secure, owing to the fact that during the floods of July last the flood-gate of the Milton drain kept the water out of this low-lying ground. On the present occasion, however, the water flowed over the low-lying bank and inundated the houses before most of the residents had any time to save their furniture and effects.29

‘The residents appear to have thought themselves tolerably secure, owing to the fact that during the floods of July last the flood-gate of the Milton drain kept the water out of this low-lying ground.’

The Brisbane Courier, 1890.30

The residents of the Milton Estate learned the hard way that a floodgate will only protect against floods to the height of the riverbank. Their floodgate had stopped the 3.75m flood of July 1889, but was ineffectual against the 5.33m flood of 1890. The people who live or own businesses in the same area today would do well to remember that their newly installed duckbills and flap-gates are subject to the same limitation (though it is possible that Coronation Drive is slightly higher in parts today than it was back then).

How did Milton end up with just one lonely floodgate back in 1889? The answer is revealed in correspondence from the Toowong Shire Council to the Central Board of Health published in the pages of The Brisbane Courier in June 1894. Responding to the board’s complaint about poor drainage in the Milton Estate, the council advised:

. . . the portion of the Milton Estate in which the nuisance is stated to exist was originally a lagoon, but during an exceptionally dry summer in 1886 was subdivided and sold in small allotments without any regard to arrangements for drainage, such subdivision and sale being a matter beyond the control of the shire council. As a necessary result as soon as wet weather set in the allotments were flooded. The shire council expended a considerable sum of money in constructing a drain to carry off the rainfall, and flood gate to prevent the reflux of the tide. This work not having been completed to the full length the drainage has only been partially efficient, though it has sufficed to remove the water to more than a foot below the bottom of what was the lagoon.31

In other words, the floodgate was built to correct for what could generously be called an oversight in urban planning. I don’t know how long the floodgate remained there, but I suspect it was deemed redundant when the drainage system was upgraded. The same correspondence explains that the shire council had “made surveys for, and are about to commence, a low level drain, which will afford relief under most ordinary conditions of rainfall”. This still begs the question, though, of why the floodgate wasn’t retained to guard against moderate flooding from the river, as it had done effectively in 1889.

How we learned to stop worrying

The title of this essay obviously goes a bit too far: nobody really loves the floods (nobody except the commercial newsmedia, anyway). But an alien observer, studying our city from afar for the last 150 years, could be forgiven for wondering why we keep letting the floods back into our lives rather than doing all we can to shut them out. And not only do we leave the door open, we keep building more things for the floods to destroy. Our observer might be led to conclude that although we make a big noise about them, we’re really not that bothered by the floods.

Of course, our alien observer would be wrong: the floods clearly do bother us. And yet, time and again, we do a pretty good job of not worrying about them. How do we explain ourselves?

Myth busters

‘Twenty years without a minor flood and 60 years without a major flood, plus a mistaken idea of the power of the dam, have made the flood risk

in Brisbane seem less than it

probably is.’

–H.W. Herbert

The Courier Mail, 1953.32

Brisbane hasn’t stood by idly in the face of the floods. We’ve built two dams, which between them have the capacity to shave a metre or two off major floods, and all but swallow up the smaller ones. And we’ve made other modifications to the river which, though done primarily to aid navigation, have also reduced the severity of floods. The success of these measures is evident from the lopsidedness of the graph shown earlier. In the 70 years between 1840 and 1910, there were about 21 floods recorded, with an average height of 4.35m and a maximum of 8.43m; in the 100 years since then, there have been just 12 floods, with an average height of 2.56m and a maximum of 5.45m.

Our mistake, it seems, lies in thinking that these measures provide more protection than they actually do. Long before the dams were built, dredging was seen by some as the answer to Brisbane’s floods. As a wrap-up of the 1887 flood in The Brisbane Courier reflected,

It has been generally believed for some years past that the extensive dredging in the lower reaches of the river would prevent a recurrence of the high floods that in years gone by have destroyed property in and around Brisbane. But the events of the past few days have shown this to be a mistake . . .33

H.W. Herbert’s warning in 1953 about the limitations of Somerset Dam (discussed above) suggests that the dam’s flood mitigation effects were similarly overestimated. And of course, the same thing happened again after Wivenhoe Dam was built. The conventional wisdom that I absorbed while growing up in Brisbane in the 1980s and 1990s was that a flood like 1974 couldn’t happen anymore — not now that the dam was built. That myth was well and truly busted by the flood of 2011. It’s probably safe to say that every major flood busts a myth like this one.

Myths like these need time to develop, and complacency needs time to set in. Over the last hundred years, there has been ample time for this to happen. Since 1910 there have been only three floods in Brisbane high enough to be categorised by the Bureau of Meteorology34 as moderate (2.6m) or major (3.5m), and these occurred 43 and 37 years apart. The longest stretch between such events in the 70 years prior to 1910 was 12 years.35 Given that much of this difference can be explained by the mitigating effects of dredging dam-building, you could almost say that we are victims of our own success in taming the river.

To lower or contain?

Broadly speaking, flood mitigation can be approached in two different ways: by lowering the river, or by containing it. The proposals discussed so far in this essay are examples of the latter: floodgates, backflow valves and levees won’t stop the river rising, but as long as it doesn’t rise too far they will keep selected areas completely dry. Dams, along with river modifications such as dredging and straightening, are examples of the former. The beauty of these measures is that they can lower the level of whole stretches of the river, reducing a flood’s footprint in all adjoining areas. Their drawback is that dams and large-scale river modifications are hugely expensive. If they didn’t provide additional benefits by bolstering water supplies or aiding navigation, it’s hard to know if they would get implemented at all.

‘it was hard for them to believe that since 1893 various schemes had been before them, and after all these Mr. Gregory practically recommended them to build second stories to their stores above flood reach.’

Meeting of the Queensland Royal Geographical Society, 1900.36

At a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society in August 1900, Sir Augustus Charles Gregory (former explorer, Surveyor General and the first resident of Rainworth) presented a paper in which he poured cold water on a proposal that had been put forward to construct a dam with a capacity of about 100 gigalitres37 (less than 5 per cent of the capacity of Wivenhoe Dam) to contain an 1893-sized flood. Gregory presented calculations to show that the proposed dam was far too small, and that a dam large enough to do the job would be beyond the means of the colony. He offered a similar opinion when quizzed about the feasibility of constructing canals to allow the river to discharge more quickly to the ocean. The gathering was clearly disappointed at Gregory’s conclusions, given the esteem in which he was held. In the words of one attendee, “it had been clearly demonstrated to them that night how quickly money could disappear in water”.

A.C. Gregory, it seems, was an advocate of neither lowering nor containing the floods, but of merely coping with them. This approach also has its merits, and judging by the number of houses that have been rasied in Milton and Rosalie since 2011, it is currently finding wide adoption. Up to 2011 though, the river-lowering approach is the one that prevailed in Brisbane. And we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that it has worked: without the mitigating effects of dredging and the two dams, the 2011 flood might have been up there with the Great Flood of 1893.38

But despite our best efforts, we can only ever shave so many metres off a flood that big. We may have reached the practical limits of our attempts to lower the river. The good news, however, is that we have tamed the river to a point where in many places (such as Milton) the banks will rarely be broken. Backflow prevention devices, perhaps supplemented with levees or raised roads, can therefore be used to great effect, providing full protection against all but the most severe floods. The time to switch to containment mode has come.

Better late than never

Venting his frustration to readers of The Brisbane Courier in 1898, Reverend John Roberts struggled to understand why such a seemingly obvious course of action as building floodgates had not been taken to mitigate floods in Milton. He attributed the inaction to shortcomings among those who were in charge:

The minds of our authorities seem sterile, or their hearts grow faint, over such matters. Perhaps they have never seen great public works of the kind, and are incapable of rising to such demands. It is to me a marvel that such a scheme as is here suggested for the districts referred to was not attempted years ago.

Roberts’ despair at the authorities of the day was probably justified. The authorities are not the only ones who have been forgetful or complacent about flood risks over the years, but they are the ones charged with taking the necessary action to manage these risks. I suspect it would have been small solace to Roberts to know that after 115 years, the Brisbane City Council is finally rising to the challenge.

If and when we do get a floodgate at Western Creek, will we trust it? Should we trust it? Will it work? Sooner or later, we will find out. For although we can never know exactly where the rain will fall, or when it will come, with floods at least one thing is certain . . .

‘We’ll meet again.’

–Vera Lynn, 1942.

UPDATE – August 2014.

Western Creek now has its floodgate. Read all about it here.

Notes:

- Duckbills have an advantage over flap-gates in that they are more resilient to siltation, which can be a problem at this part of the Brisbane River. I’m not sure why both types of device have been used at this particular location — perhaps it is to see which is more effective. ↩

- A concept design for this system is presented in this document from the council’s Stage 2 investigation. ↩

- Under current conditions — that is, with Wivenhoe and Sommerset dams in operation — the 2011 flood level has been modelled to have an average recurrence interval (ARI) of 120 years. Under pre-dam conditions, the ARI is modelled to be 100 years. (Mark Babister and Monique Retallick (2011), Brisbane River 2011 flood event — Flood frequency analysis, Final report submitted to the Queensland Flood Commission of Inquiry, Sydney: WMA Water, p35. Accessed online on 16 December 2012.) ↩

- In fact, so much water floods this area that the report submitted to the council recommends “that Council investigate the impacts of removing the flood storage provided by this system on the river system as a whole”. In other words, if the water doesn’t go here, its impact might be felt somewhere else. ↩

- MWA Environmental (2011), Brisbane backflow prevention measures investigation: Pre-feasibility study, Volume 1, prepared for Brisbane City Council, p82. Accessed online on 16 December 2012. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 10 February 1898, p6. ↩

- Mark Babister and Monique Retallick (2011), Brisbane River 2011 flood event — Flood frequency analysis, Final report submitted to the Queensland Flood Commission of Inquiry, Sydney: WMA Water, p10, accessed online on 16 December 2012. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 13 June 1893, p5. ↩

- Allan T. Miles (1980), Rosalie – ‘Brisbane’s Forgotten Daughter’, presented to the Royal Historical Society of Queensland. Accessed online on 29 December 2012. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 20 November 1900, p7. Soon after this date, his name starts popping up in Hobart’s newspaper, The Mercury. ↩

- Other letters from Roberts concerning Red Jacket Swamp include those published on 17 November 1896, 17 May 1898, and 25 May 1898. ↩

- The Reserve Bank’s pre-decimal inflation calculator suggests that this equates to around $1 million in today’s money. But I don’t know how reliable this estimate is! ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 10 February 1898, p6. ↩

- Mark Babister and Monique Retallick (2011), Brisbane River 2011 flood event — Flood frequency analysis, Final report submitted to the Queensland Flood Commission of Inquiry, Sydney: WMA Water, p30, accessed online on 16 December 2012. In 2011 the Port Office gauge actually recorded 5.27m at the peak of the flood while the City Gauge, which is situated on the opposite bank of the river, recorded 4.46m. This discrepancy does not appear to have been fully resolved, but the Flood Commission of Inquiry has since adopted the City Gauge reading on the grounds that it is the most likely to be correct. See page 522 of the Commission’s final report for more detail. ↩

- Babister and Retallick (2011) (page 30), drawing on the work of others, suggest that the river works done since 1890 would reduce the 1890 flood to just 3.8m at the Port Office gauge, instead of 5.33m. Wivenhoe and Somorset dams would reduce this peak even further. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 11 February 1898, p6. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 15 February 1898, p2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3666485 ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 11 February 1898, p6. ↩

- Alas, this doesn’t lend itself so well to a palindrome. The best I can do is “Not lime tag do ol fa floodgate Milton”, which is, of course, appalling. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 24 July 1889, p3. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 17 October 1890, p5. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 26 May 1909, p6. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 24 July 1889, p3. ↩

- Herbert, according to the article, was a staff member of the Bureau of Industry, where he “made a special study of Brisbane River flood risks”. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 4 March, 1953, p2 ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 4 March, 1953, p2 ↩

- According to the Wikipedia article, the construction of Wivenhoe Dam had actually been approved in November 1971. Presumably though, the 1974 flood upped the ante somewhat. ↩

- The Courier Mail, 4 March, 1953, p2 ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 17 March 1890, p6-7. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 17 March 1890, p6-7. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 14 June 1894, p2. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 4 March, 1953, p2 ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 24 January 1887, p5. ↩

- Search for ‘brisbane city’ on this page. ↩

- This period of 1875 to 1887 included a flood of 2.46m in 1879. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 22 March 1900, p6. ↩

- A gigalitre is one thousand million litres. The article actually refers to a dam of twenty-five thousand million gallons. ↩

- Mark Babister and Monique Retallick (2011), Brisbane River 2011 flood event — Flood frequency analysis, Final report submitted to the Queensland Flood Commission of Inquiry, Sydney: WMA Water, p30, accessed online on 16 December 2012. ↩

Last modified: August 26, 2023

Very interesting article.

I’m wondering if similar studies have been done for rural cities.

In the 2011 floods Maryborough had similar back flow problems that cut off important areas in the city that were normally isolated from the river.

Another great article – as usual well researched and entertainingly written

Pingback: Update | DJ GLAD RAPPA

The nearly completed Wivenhoe saved Brisbane from an estimated 8 metre flood in the city, much higher than 1974. History does not take this into account and assumes 1974 is the highest recent flood.

Pingback: A floodgate for Western Creek | There once was a creek . . .

Pingback: The legend of the lost lagoon | There once was a creek . . .

Pingback: Are we learning yet? | There once was a creek . . .

bi57wu

cgxawm

6uunsn

cu00bg

vyzdox

great

lvxlig

pwd562