From Red Jacket Swamp to Rosalie’s playground:

The story of Gregory Park

Page 1 – Page 2 – Page 3 – Page 4 – Page 5 – Contents

What would Rosalie be without Gregory Park? If Rosalie is really a village, then Gregory Park is the village green, a place where the neighbourhood seems to become a community. To see this place teeming on a Sunday afternoon with all manner of recreation — people playing cricket, soccer or Frisbee, having barbecues, jogging, or just relaxing under the Moreton Bay figs — it’s hard to imagine that things were ever any different.

Yet buried just a few feet beneath this park is a story of dramatic transformation. It is a story of how a watercourse was first polluted and defiled, then feared and hated, then finally mastered and modified by the population that grew up around it. Perhaps no other landmark in the Western Creek catchment can better illustrate the challenges of urbanising a natural landscape, or the scale of changes wrought in doing so, than Gregory Park. And certainly no other landmark in the catchment has been the cause of so much conflict and controversy, or such discomfort and discontent. This is because the story of Gregory Park is also the story of Red Jacket Swamp.

1. There once was a swamp (1850s – 1880s)

At the bottom of the Government House grounds, and reaching under Baroona Road into Norman Buchan Park, is a small pond. This pond is one of the few remaining fragments of Western Creek, which began in the hills of Rainworth and flowed through Rosalie and Milton to meet the Brisbane River where Milton Drain does today. Between this pond and the Brisbane River, Western Creek was once braided by swampland, forming even during dry seasons a “chain of ponds”, as John Oxley observed during his exploration of the Brisbane River in 1824.

The low rich land (1855)

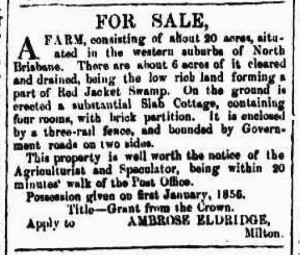

This swampy stretch of Western Creek became known as the Red Jacket Swamp. The earliest reference to this name that I have found is in an advertisement placed in The Moreton Bay Courier in 1855 by Ambrose Eldridge, who was selling his ‘Milton Farm’:

Eldridge was a pharmacist who ran a drugstore in Queen Street up until about 1853, when he turned his attention a series of agricultural ‘experiments’ that included a prize-winning cotton crop. He had bought this land in 1851 and on it built Milton House, which still stands (albeit partly reconstructed) tucked away in the office park near Park Road. He sold Milton Farm in 1856 to relocate to his other property at Eagle Farm.

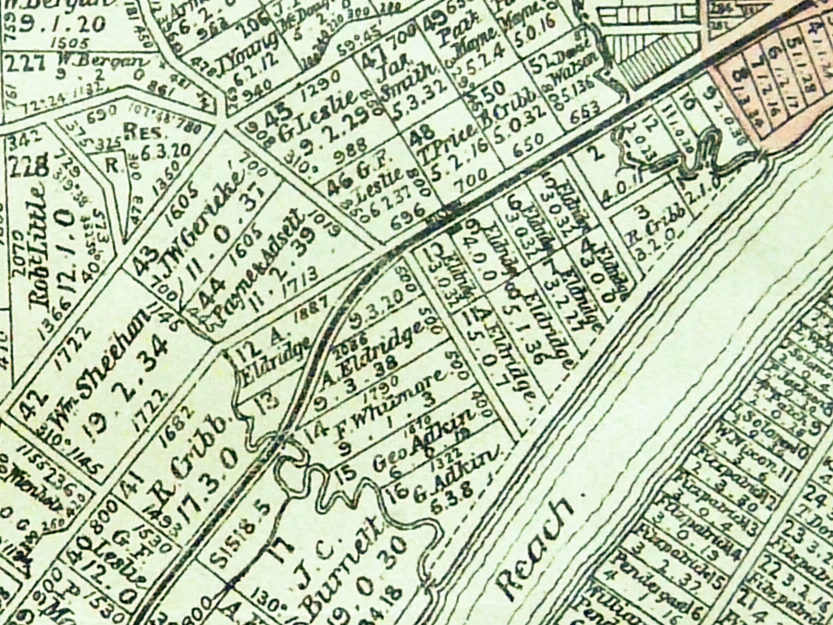

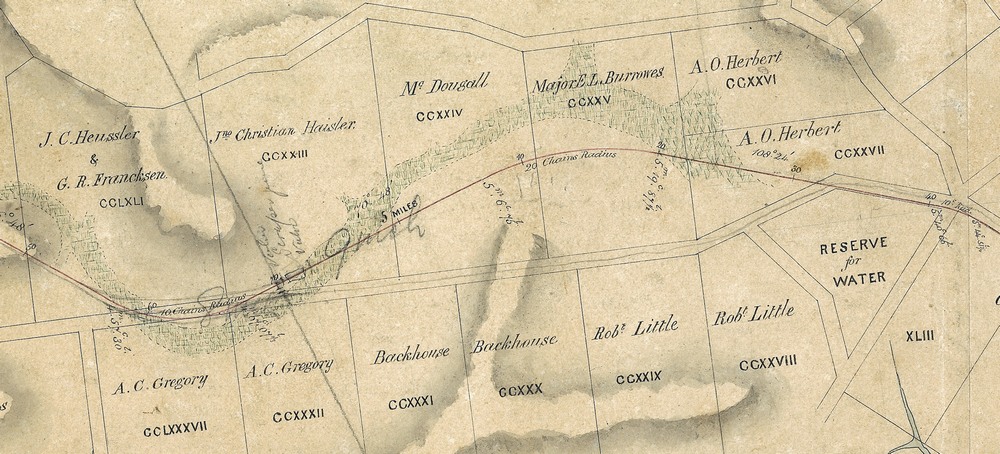

The map below indicates Eldridge’s original land holdings in the area. Among them are two blocks dissected by the railway line and bordered by Western Creek. These are most likely the blocks containing the land described in the advertisement as the “six acres . . . cleared and drained, being the low rich land forming part of Red Jacket Swamp”. In any case, the advertisement confirms that the name ‘Red Jacket Swamp’ was once used to describe an area between Milton Road and the river.

The area of present-day Milton, as depicted on a Brisbane parish map held by the Brisbane City Council Archives. (The map was published around 1900, but is thought to show the original land grants.)

A spring of the purest water (1864)

Another early reference to Red Jacket Swamp appears in a petition sent to the Secretary for Land and Works in 1864 by J.C. Heussler, who was one of the early residents in the area and the first owner of Fernberg, which later became Government House. The petition was signed by local land owners, residents and farmers, and humbly begged “that a Water Reserve may be formed at the Red Jacket Swamp . . . where there is a spring of the purest water upon which the inhabitants (some hundreds, and daily increasing) have been entirely dependent during the late drought”.1

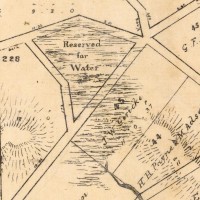

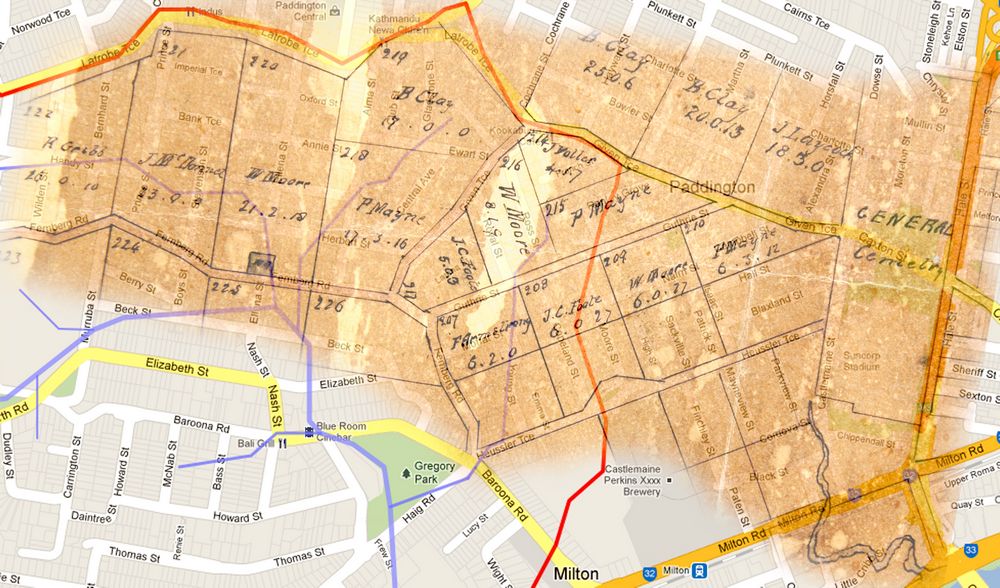

A map included with the petition shows the location of the spring to be at the intersection of Fernberg Road and Ellena Street. The figure below shows part of this map superimposed on a modern-day street map. Also shown is the approximate path of Western Creek and its tributaries, derived from digital elevation data.

A map accompanying an 1864 petition overlaid on Google Maps. The proposed water reserve can be seen on Fernberg Road, to the left of the picture. (The original map is held at the Queensland State Archives, ID22054)

This part of the creek — indeed, any part upstream from Gregory Park — is generally not depicted even on the earliest surviving maps. The only exception that I have found is a map that currently hangs in the Brisbane City Archives showing the proposed route of the water mains from Enoggera Creek Reservoir to the Town of Brisbane, a part of which is reproduced below. The shaded region on this map corresponds with the path of Western Creek through Rosalie, Fernberg and Norman Buchan Park.

The swampy area of Western Creek (shaded) passing through what is now Norman Buchan Park, Government House (J.C. Heussler’s property) and Rosalie. The map is dated 1864 and titled “Plan of Brisbane Water Works”. It shows the pipeline route between Enoggera Reservoir and Brisbane City, and is hanging in the Brisbane City Council Archives.

Taking into account Eldrige’s advertisement and the map with Heussler’s petition, we can conclude that in the middle of the 19th Century, the name ‘Red Jacket Swamp’ was used to describe the stretch of Western Creek from the river up to at least Fernberg Road. Quite possibly, the swampland extending to Norman Buchan Park was known by this name as well.

Refining the boundaries (1886 – 1890)

As the Rosalie and Milton area developed, the boundaries of what was called Red Jacket Swamp became more specific. At the upstream end, a distinction was being made between “the Rosalie and Red Jacket Swamps”2 at least as early as 1886. This probably reflected a narrowing of the swamp near the junction of Baroona Road and Bayswater Street, but the presence of Baroona Road itself (then known as ‘the Boundary-road’ between Ithaca and Toowong shires) might have reinforced the demarcation.

Downstream, the construction of what is now Haig Road (then referred to as an extension of Heussler Terrace) may have helped to define the boundary. I’m yet to find a map without this road drawn on it, implying that it existed in some form at an early stage. However, for a time it was probably just a track through the swamp. In July 1888, the Toowong Shire Council received correspondence “from W. H. Spode and others, asking that a road may be made across Red Jacket Swamp, alongside suburban allotment No. 43”.3 By March 1890 this must have happened, as a report on a flood stated that “A portion of Heussler-terrace, from the Boundary-road to Bayswater-street, being one of the boundaries of the Red Jacket Swamp, was entirely submerged”.4

Thus, whether as a reflection of natural boundaries, built ones or both, ‘Red Jacket Swamp’ came to be known as the area bounded by Bayswater Street, Baroona Road and Haig Road — that is, the site of Gregory Park and Milton State School. Looking at the surrounding topography, it is easy to imagine this site as the central link in John Oxley’s chain of ponds. Here, all of the water draining from the surrounding hills of Rosalie, Torwood and Paddington, and indeed from the whole catchment extending up through Rainworth and Bardon, would have met and mingled with the tidal inflows of the Brisbane River.5

But this all begs the question: why was it called “Red Jacket Swamp” in the first place?

The legends of Red Jacket Swamp

The earliest account that I have found of how Red Jacket Swamp acquired its name is an article that appeared in The Queenslander on 20 May 1893 entitled “The Legend of Red Jacket Swamp”.6 The author (listed simply as ‘Clare’) tells of a time when “little boys were clothed by their mothers in 50lb flour bags” and played hide and seek in the Paddington cemetery (which later became Lang Park). Two boys thus clothed were one day chasing a frog about the large swamp in Milton when one fell into “a peculiar-looking pool of water, which apparently was tinged a dark red by the infusion of some mineral substance—probably iron”. When the boy emerged, his white flour jacket was dyed a dull red. This accidental fashion statement created a sensation among his peers, who were quick to follow by dipping their own flour-bag jackets in the pool. And so the legend of the Red Jacket Swamp was born.

Or was it? The author of a historical essay about Milton and Rosalie in The Brisbane Courier nearly forty years later seems not to have heard the flour bag story, but evidently had heard a few others:

A curious legend has persisted that Red Jacket Swamp was named after a soldier’s red jacket which its luckless wearer lost in the locality, but the true explanation, according to old residents, is that the swamp received its name from a small flower-like weed that flourished in its muddy waters; during certain months of the year the leaves — no larger than a threepenny piece — would change in hue to brick red.7

Fast-forward another forty or so years, and the topic is touched upon again in Allan Miles’ History of Rosalie.8 With at least three different legends of Red Jacket Swamp to choose from, Miles adds yet another, stating that the name originated from a species of bird that lived in the swamp.

Which legend is true? There is no reason (that I know of) to doubt that both red-jacketed birds and red-leaved waterweeds might have been found at the swamp (incidentally, there were also red-bellied black snakes9) — but whether either of these actually gave rise to the swamp’s name is another question. The little boys’ flour-bags and the soldier’s red jacket certainly present more literal explanations for the name, but I don’t know enough to discount or confirm either of them. Writing nearly forty years after Allan Miles, I feel almost obliged to carry on the tradition and propose yet another legend of Red Jacket Swamp — but four ought to be enough.

Plump booty (1860s)

In the mid nineteenth century, Red Jacket Swamp and the fledgling population of Rosalie appeared to have a relatively healthy coexistence. Indeed, as mentioned earlier, during a drought in the 1860s many local residents depended on a part of the swamp (though most likely it was upstream of Gregory Park) as a source of clean water.

The swamp was also a source of food, not just for indigenous people but also for some of the early European residents. A historical article in The Brisbane Courier in 1931 reminisced about

. . . the red-billed water hens and the snipe that made the tea-trees and bulrushes of Red Jacket Swamp their rendezvous. Many a morning Mr. J. A. Cumes, of Baroona Hill, one of the earliest residents in the district, would bring plump booty home, the reward of patient lurking among the reed-fringed banks of the watercourse. “If I had no luck at the Swamp,” said Mr Cumes, “I would go over to Toowood, and come home with some curlews.10

(Incidentally, you can still find curlews wondering about Frew Park and Milton Park sometimes if you pass by in the evenings.)

Into the quagmire (1880s)

Red Jacket Swamp’s days were numbered as soon as the settlement of Brisbane began to spread along the Milton reach of the river. You could even say that it had it coming from the moment John Oxley noted in his 1824 diary that this “chain of ponds” was “by no means ineligible as a station for a first settlement up the river”.11 While some creeks manage to retain a place in the matrix of urban development, swamps almost invariably do not. Besides taking up valuable (albeit flood-prone) real estate, swamps are liable to become a nuisance and a hazard to people living around them — especially once they become the receptacle of those same people’s rubbish and sewage.

By the mid 1880s, the population of the Rosalie area (and of the greater Brisbane settlement) had burgeoned, and so too had the amount of sewage and other waste entering the swamp. Agitations for the swamp to be drained started to come from all directions — Ithaca and Toowong ratepayers,12 the Central Board of Health,13 even the Queensland parliament.14 In April 1887, the Toowong Shire Council received a petition “from J. G. McNab and seventy-nine others, asking for the drainage of Red Jacket Swamp, and for the council to take steps to get the entire control of the reserve”.15

At about the same time, moves were being made to secure a site for a new school in the Rosalie area. The preferred site was an area towards the top of Howard Street, but acquiring the necessary land was deemed too expensive. The next best option was the dry ground skirting Red Jacket Swamp along Bayswater Street, which despite obvious drawbacks “had the decided advantage of being free of cost”.16 The necessary arrangements to secure the site as a school reserve were in place by mid-1886, though construction did not commence until 1888 and classes not until 1889.

The construction of the school next to the swamp brought a new level of outrage and urgency to concerns that, like the swamp itself, were already festering in the community. The following letter, signed “Sanitary”, appeared in The Brisbane Courier in September 1888:

Sir,—On the knoll above the Red Jacket Swamp, at Milton, is being erected a large school under the supervision of the Education Department. Allow me to draw your attention to the unsanitary state of the quagmire, but a few feet from the building. It is inexcusable to allow a building of this kind to be erected where a large number of healthy children will assemble for five hours a day to inhale the noxious exhalation arising from the filthy drainage which accumulates in this spot from Rosalie.17

There would be many more letters and petitions sent, committees formed and stormy public meetings held before this issue was resolved. If you think a Telstra tower next to a school is bad news, then you ain’t seen nothing.

Next page

Page 1 – Page 2 – Page 3 – Page 4 – Page 5

Contents

Notes:

- Miles, Allan T. (1978), A history of Rosalie, Eastwood, NSW. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 4 March 1886, p5. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 5 July 1888, p3. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 17 March 1890, p6. The “Boundary-road” is what we know today as Baroona Road, which was the boundary between the Toowong and Ithaca shires. ↩

- Tidal water was entering the swamp in the late 19th century, but by then the river had already been modified through dredging to improve access for shipping. It is possible that in 1824 the tides did not come up as far (see this post for more discussion). I’d love to hear from anyone who can shed some light on this matter. ↩

- “The Legend of Red Jacket Swamp”, The Queenslander, 20 May 1893 ↩

- “Milton and Rosalie”, The Brisbane Courier, 30 May 1931, p19. ↩

- Miles, Allan T. (1978), A history of Rosalie, Eastwood, NSW. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 6 March 1894, p5. A letter to the editor recounts an incident “some years ago” when a snake, black on the upper side with red rings underneath, came out of the swamp and was tackled by a large dog, which about an hour afterwards was dead. ↩

- “Milton and Rosalie”, The Brisbane Courier, 30 May 1931, p19.” ↩

- See note 1 ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 28 April 1887, p5. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 4 March 1886, p5. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 29 October 1886, p2. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 28 April 1887, p5. ↩

- Miles, Allan T. (1978), A history of Rosalie, Eastwood, NSW ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 29 September 1888, p9. ↩

Last modified: August 26, 2023